Overview of First and Second Nephi

This overview of 1 Nephi and 2 Nephi is because I have been

asked to post things that will run with the course of study

for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for

this upcoming year. The subject is the Book of Mormon,

and it begins with Nephi's writings.

Those who follow this blog who are not members of the Church of

Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the Mormons) will profit

from this posting for two important reasons. First, you will

understand why I am a Mormon and believe so strongly in the

Church and, second, you will gain a perspective on how the

bible, like the Book of Mormon, must be read to be understood.

This overview is, in my view, essential if one, whether Mormon

or not, wants to understand what Nephi and other writers in

the Book of Mormon have to say. Too few members of the Church

(meaning the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) even

suppose there is something below their superficial view of the

Book of Mormon. The Church lesson manual, Come Follow Me, does

not promote the sort of study the book deserves. This blog will.

And this overview of the first two books of the Book of Mormon,

which provides the same needed overview of biblical writing, is

fun to read because it has some illustrative videos.

I will continue with posts to this blog as the study of the

Book of Mormon progresses through the year by making posts

that correlate with Come Follow Me. These postings will be far more

profitable for you who are not Mormons if you get a copy of

the book and read the parts on which I blog. The first two

books of the Book of Mormon are only 116 pages, so anyone

can quickly get the gist of these two books in very little time,

but an in-depth appreciation for what is there will take more

than quick read. But read these two books quickly after you have

this blog, and you will see things (if you are a Mormon) you

have never seen before.

I want comments about these postings, because I want to know

what readers think. It will help sharpen my focus and thoughts.

So do not be shy. I cannot be offended.

I hope to publish my Exegesis of the Book of Mormon within a few

years, so this is a good exercise for me and better if I get comments.

One final, introductory comment before you read on. It has been

suggested by some that I write a little more simply. (Most books are

written at about the eight-grade level.) I am not going to do that.

I write at my level of learning, including my vocabulary. You just

need to stretch a little, and part of that may be having a dictionary

at nearby.

I like this quote of Hugh Nibley when he was being inter-

viewed in 1995 by Gregory A. Prince. Nibley wrote the priesthood

manual for he church in 1957, An Approach to the Book of Mormon.

The Church writing committee thought it over the heads of the members,

so it was rejected. Nibley recounts, "They wanted to make hundreds of changes

and get rid of the whole thing entirely, and President McKay said,

'No. If it's beyond their reach, let them reach for it.' Adam S. Bennion

[the head of the writing committee] said, 'It's over their heads.'

And President McKay said, 'Let them reach for it. Now there's a

great man. I liked that."1

Overview of 1 Nephi and 2 Nephi

Nephi began writing the small plates of Nephi thirty or forty years after the emigration from Jerusalem.2 He had been keeping a record of the proceedings of the emigrants on a different set of plates called the large plates of Nephi. This other set of plates contains the history of the people, “And if my people desire to know the more particular part of the history of my people they must search mine other plates.”3 Rather than a history, Nephi’s small plates were for what was “good in [the Lord’s] sight, for the profit of [his] people. . . . that which is pleasing unto God.”4 Nephi wrote the small plates, then, so his people during his day could profit from what was pleasing to God.

Mormon was impressed with the small plates, and it is because of his characterization of them as a small account that they are called the small plates.

And now, I speak somewhat concerning that which I have written; for after I had made an abridgment from the plates of Nephi, down to the reign of this king Benjamin . . . I searched among the records [and] found these plates, which contained this small account of the prophets, from Jacob down to the reign of this king Benjamin, and also many of the words of Nephi.5

The small plates are an account of the prophets according to Mormon, so he, also, differentiated these plates from a history. Mormon was so impressed with this account of the prophets he just appended it to his abridgment of the large plates of Nephi.6 So Nephi’s two books were not abridged. We have them as Nephi wrote them.

The reason the Lord wanted today’s readers to have these two books in their unabridged form is not explicitly stated. Mormon said they contained fulfilled prophecies about the Savior and events from Nephi’s time to Mormon’s. And Mormon prayed that the small plates would help the descendants of his brethren return to a knowledge of God and the Savior’s redemption. “[T]hey are choice unto me, and I know they will be choice unto my brethren. . . . my prayer to God is concerning my brethren, that they may once again come to the knowledge of God, yea, the redemption of Christ; that they may once again be a delightsome people.”7

So what is it in this unabridged record that helps the descendants of Mormon’s brethren, the Lamanites, return in our day to a knowledge of God and the Savior’s redemption? How do Nephi’s two books contribute to this hope? And why did Nephi divide his record into two books?

The role of 2 Nephi is not difficult to see It is prophetic and doctrinal and empowering and self-proving. It is prophetic in the sense it foretold8 and foretells9 what would and will happen if Nephi’s people did not and we do not follow Christ. It is and doctrinal because it explains the doctrine of Christ.10 It explains the empowerment that comes from the gospel.11 And it is self-proving because it shows the fulfillment of prophecy both then12 and today.13

Nephi’s first book is nothing like 2 Nephi. It is, indeed, a series of events as the emigrants left Jerusalem and journeyed to the land of promise, so many suppose it is a history.14 But such a supposition is superficial because it overlooks what 1 Nephi has that one does not typically find in a history: 1 Nephi is full of allusions, metaphors, and figures of speech.17 the words, the events in 1 Nephi carry the message pleasing to God for Nephi’s people and, by extrapolation, today’s people. The events, therefore, are like the pixels in a digital image or the dots in a lithograph, each pixel and dot adding to what was for the benefit Nephi’s people and readers today. The events are the vehicle for the message or tenor of meaning.

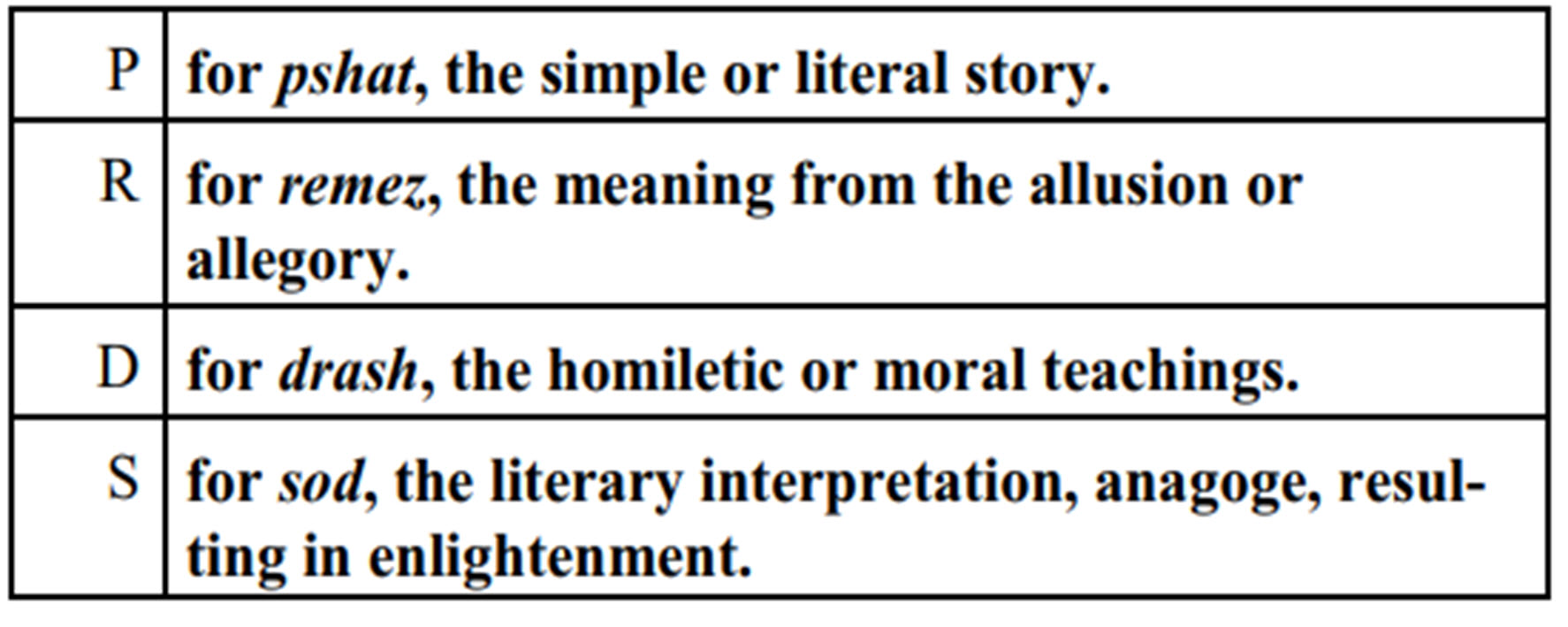

There is Rabbinical approach to ancient scriptures that can assists the Book of Mormon reader. Rabbinical exegesis has four traditional levels described by a Persian word, prds or pardes.18

There is Rabbinical approach to ancient scriptures that can assists the Book of Mormon reader. Rabbinical exegesis has four traditional levels described by a Persian word, prds or pardes.18

These levels of analysis may be applied to the Book of Mormon even though one should not presume that the prophets intentionally wrote with these levels of meaning in mind. This is just an interesting tool or methodology for study. The scriptures, it seems to this author, should be an encounter with prds or, by adding vowels between the letters, an encounter paradise.

The second thing to keep in mind is more difficult, perspective. What one gathers from the events Nephi put in his first book is dependent upon one’s perspective. If one is just looking for the dots or pixels, the literal meaning, one will not see what was written. A different approach is required. One must view the events in Nephi’s record from Nephi’s perspective, meaning both his intention, the prds analysis, and his view of metaphysics, how he viewed reality.

The foregoing video clip helps appreciate the importance of viewing what Nephi wrote from his perspective. The image is of the same 1,252 painted balls suspended from a ceiling, artwork by Michael Murphy. But what is seen depends on the perspective of the viewer.19 The Western metaphysical perspective separates the idea of something—the adjoining portrays an eye—from what is actually there—balls suspended from a ceiling. The Hebrew metaphysical perspective does not separate the idea of a thing from the thing itself: they are the same thing,

[T]he Bible does not possess a clear division between words or thoughts and the objects to which they refer, but rather understands man’s reality as consisting of davarim, an intermediate category between word and object that may be called an understanding or an object as understood.”20

Actually hearing a voice and thinking about a voice are the same from the Hebrew perspective or metaphysical paradigm. Nephi and other Old Testament writers could say they heard the voice of the Lord when, from the Western perspective, all Nephi did was think about the Lord talking or imagine what the Lord would say in a particular circumstance, which is something a prophet does.21 Likewise, actually seeing a person would be the same from Nephi’s perspective as thinking about the person being present.

The Hebrew metaphysical paradigm—the metaphysical paradigm effecting the Book of Mormon—must be understood if the Book of Mormon is to be understood. The metaphysical paradigm does not effect the meaning, but it does affect one’s perception of what is written and, therefore, one’s understanding. Without the right perception of what happened when events are described, the reader is likely to misapprehend the meaning. Therefore, the reader must understand both the perspective of the writer and the reality that the vehicle or events used to carry the message may have been adjusted to comport with the message. The vehicle may not literally be true from the Western metaphysical perspective.22

The challenge for the reader is deciding when events are being used as a vehicle requiring the reader to focus on meaning that must be discovered within the words or between the lines rather than thinking the vehicle is something that actually happened.

An example helps appreciate the difference between actual facts and a vehicle that should not be seen as true. The first verses of say Nephi was born of important or well-to-do parents—goodly is the word used to describe Lehi’s status—so that he was well educated: his parents could afford to send him to school.

I, Nephi, having been born of goodly parents, therefore I was taught somewhat in all the learning of my father; and having seen many afflictions in the course of my days, nevertheless, having been highly favored of the Lord in all my days; yea, having had a great knowledge of the goodness and the mysteries of God, therefore I make a record of my proceedings in my days.23

There is no particular message in this declaration. It is background facts. The reader, therefore, can take these facts as true; indeed, should take them as true because they are the setting for what follows.

What follows—Nephi’s description of his father’s prayer—has a different tenor. Nephi describes his father’s prayer using figures of speech and allusions to Old Testament events. What Nephi wrote is esoteric to a reader who is unfamiliar with the Old Testament and Hebrew metaphysics because the Western reader tends to view the writing from a Western perspective that makes seeing and hearing something different than thinking. So this description of Lehi’s prayer is cryptic to the typical modern-day reader who does no appreciate how Nephi uses figures of speech, which are bolded below, to pack a great deal into what he says about his father’s prayer in a few words.

And it came to pass as he prayed unto the Lord, there came a pillar of fire and dwelt upon a rock before him; and he saw and heard much; and because of the things which he saw and heard he did quake and tremble exceedingly.24

Did an actual pillar of fire come from somewhere and dwell—what does dwell mean?—upon a rock in front of him? Or is the pillar of fire metaphorical, an allusions to events in the Old Testament? Is it significant that this pillar is described as a fire?

Pillar of fire is something well-known to anyone who as seen the 1956 version of “The Ten Commandments” by Cecil B. DeMille, because he portrays the pillar of fire that protected the Israelites from Pharaoh’s advancing army in a theatrical way.

Interestingly, DeMille employed Arnold Friberg , a member of the Church, to paint the pictures used by DeMille to storyboard and design the sets and direct the film. Friberg’s paintings preceded and were duplicated in the film. An interview of Friberg about this follows:

What we have in the 1956 movie, then, is Friberg’s artistic conception of the pillar of fire. DeMille’s 1923 silent-version of “The Ten Commandments” portrays the pillar of file as a wall of fire:

(The actual scene with the wall of fire begins just after 04:23 in this 06:33 excerpt. The excerpt is longer than the wall-of-fire scene because it is interesting to compare what DeMille did in 1923 to what he did in his last ever film production in 1956.)25

Hopefully, no one actually thinks DeMille’s portrayal is what really happened; after all, it is a Hollywood movie. So the question is whether DeMille’s portrayal or the similar portrayal’s of the pillar of fire before Lehi in the Church video are accurate or misleading? The Church produced videos in 2019 that theatrically portray events in the Book of Mormon. The Church-sponsored video about Lehi’s prayer before he left Jerusalem is not quite as dramatic as DeMille’s portrayal of the pillar of fire (the Church video did not have the same budget, apparently), but it is still just the idea of a movie maker who viewed what Nephi wrote from the Western metaphysical perspective that demanded the occurrence of something literal: a focus on the vehicle of the metaphor rather than the tenor. The Church video about Lehi’s dream interprets Nephi’s metaphor literally, as a pillar of light that shined on Lehi while he was on a rock.

The answer to the question whether the video of Lehi’s prayer is accurate is, well, no. The video not only misses the point, it is misleading in that it makes literal what was not and, thereby, obfuscates Nephi’s intended meaning. (One cannot make a movie of a metaphor’s vehicle.) The video is especially unfortunate because it is dramatic and makes such a mental impression it staunches further inquiry and discussion about the meaning of the vehicle, the metaphor. Moreover, readers will despair of having experiences like Lehi’s even though unpacking the metaphor says the reader can have thr exact experience Lehi had. The supernatural gloss in the Church video is inconsistent with how the Spirit operates and what happened to Lehi as he prayed.26

Whether in the Moses story or what Nephi wrote about his father;s prayer, the meaning or the tenor of pillar of fire, a metaphor is what is important. Nephi’s allusion to the pillar of fire that protected the Israelites by night—in the darkness—means Nephi intended to tap into the knowledge of the reader and, thereby, leverage the reader’s understanding of the metaphor to describe his father’s prayer with more force and impact than otherwise possible.

This leverage extends to the word rock, which is the vehicle for a well-known metaphor used in the scriptures: the tenor is the Savior or the rock of our salvation. This tenor of the rock metaphor was well-known by Nephi and his father, but it is something that must be understood or even seen as a metaphor before today’s reader can see and hear the meaning of this metaphor and how to synergize the rock metaphor with the pillar-of-fire metaphor. What, in other words, is the meaning of the pillar of fire that dwelt upon a rock?

The synergy of these two metaphors is emphasized by the verb dwelt. The pillar of fire dwelt upon a rock. The typical sense of dwelt is something like live or reside or to exist or be present, so the reader will think of this pillar of fire resting or sitting on a rock if the reader’s mind is biased in favor of an actual event. However, dwelt is also defined as to linger over something (as with the mind or eyes),27 in which case this verb is used with the words on or upon. Thus, dwelt upon means a mental lingering about the tenor of the rock metaphor, the Savior.

The Hebrew metaphysical perspective of reality for someone like Nephi, also, complicates this verse. The complicating parts are bolded:

And it came to pass as he prayed unto the Lord, there came a pillar of fire and dwelt upon a rock before him; and he saw and heard much; and because of the things which he saw and heard he did quake and tremble exceedingly.28

Saw and heard is an hendiadys, so the meaning of this single term cannot be parsed by splitting the verbs apart to say that Lehi’s eyes saw something and that his ears heard something. Like any figure of speech, an hendiadys expresses a single complex idea that neither component of the word—an hendiadys should be viewed as a single word—can express separately. As such, the idea expressed by this hendiadys, like any figure of speech, would require many more words to convey the meaning conveyed by the more economical hendiadys.

The meaning of this hendiadys and the particular figures of speech in the foregoing pregnant verse will be explored in conjunction with the exegesis of this part of Nephi’s writing. Suffice it to say in this overview that most do not see the difference between things that may be taken literally (as factual) and things that can only be seen and understood (note the use of this hendiadys) by reading between the lines or understanding the figures of speech used to express the compacted meaning intended by Nephi from his perspective of reality.

If a reader does not unpack Nephi’s compacted writing because the reader does not see and hear what Nephi wrote—the reader is not familiar with the Old Testament enough to recognize the allusions and metaphors—then the reader cannot understand what it is that Nephi was trying to say. Such a reader is left with only one alternative when searching for meaning: attach literal meaning or none at all to these figures of speech and allusions.29

The foregoing underscores this reality: Nephi’s first book is, indeed, nothing like 2 Nephi. It is a series of events as the emigrants left Jerusalem and journeyed to the land of promise. This exegesis views the events in 1 Nephi for what they are: experiences where the emigrants were led by the Spirit to escape destruction. In other words, the events in 1 Nephi show how the Spirit operated for them, and, by extension for us today. Gathering from these events how the Spirit operates enables one to appreciate the testimonies of the Savior in the second part of Nephi’s book, 2 Nephi. The tutelage of 1 Nephi is why it is different than the doctrinal exposition in 2 Nephi.

Endnotes

- Gregory A., Prince, "David O. McKay and the 'Twin Sisters': Free Agency and Tolerance," Dialogue, A Journal of Mormon Thought, https://www.dialoguejournal.com/articles/david-o-mckay-and-the-twin-sisters-free-agency-and-tolerance/

- Nephi comments on this second record at 1 Nephi 10:1, and 2 Nephi 5:28–33 says this record was not begun until thirty years after the emigration. Nephi began this second record after the death of Lehi and the division of Lehi’s family into the Nephites and Lamanites.

- 2 Nephi 5:33. Joseph Smith did not see these other plates, and, of course, neither they nor the small plates are available today.

- 2 Nephi 5:30, 32. Nephi’s brother, Jacob, warned the Nephites about their sins and the awful consequences of sin. He said he could not write “a hundredth part of the proceedings of this people . . . upon these plates; but many of their proceedings are written upon the larger plates . . . .” Jacob 3:13.

- Words of Mormon 1:3 (emphasis added).

- Words of Mormon 1:6. This appendix is something like an excursus added during the course Mormon’s abridgement of the plates of Nephi; apparently, he appended the small plates before he continued his work on the rest of the Nephite records. Mormon says,

[A]fter I had made an abridgement of the plates of Nephi, down to the reign of this king Benjamin . . . I found these plates [about the prophets from Jacob until king Benjamin, including Nephi, so] I chose these things, to finish my record about them.

Words of Mormon 1:3, 4, 5 (the antecedent of them is the identified prophets.

- Words of Mormon 1:8.

- Lehi warned Laman and Lemuel of their misery if they did not hoe to the gospel and Nephi’s leadership. 2 Nephi 1:9–29. Lehi promised prosperity or cursing based on adherence to the commandments. 2 Nephi 4:3–5. Lehi prophesied that the emigrants would not be totally destroyed notwithstanding their wickedness. 2 Nephi 4:6–79.

- Lehi says the Americas are consecrated for the righteous who will never be taken captive if they keep the commandments. 2 Nephi 1:7–8. The quotations from and explanations of Isaiah. 2 Nephi 7–ch. 24. Nephi’s explanation of Isaiah’s prophecies as they relate to the world and, in particular, to Nephi’s people. 2 Nephi 24–ch. 26:11, and in he latter days, 2 Nephi 26:12–ch. 30.

- Lehi explains redemption through Christ. 2 Nephi 2. Nephi conclusion, which is about the Savior and the Holy Ghost, defines the gospel as the doctrine of Christ. 2 Nephi 31–ch. 33.

- Nephi’s monologue, a dithyramb praising the Lord, shows how the hope of eternal life enables one to overcome the sorrows and burdens of this life. 2 Nephi 4:13–35.

- Lehi’s and Jacob’s vision of the destruction of Jerusalem. 2 Nephi 1:4, 6:8. The separation of the Nephites from the Lamanites and the contrasting prosperity and cursing of the two groups. 2 Nephi 5. The ongoing battles and eventual destruction of the Nephites is not contained in the small plates, but the remaining parts of the Book of Mormon show the fulfillment of prophecies made in 2 Nephi.

- Joseph of Egypt’s fulfilled prophecy of Joseph Smith. 2 Nephi 3. The prophecies of Isaiah in 2 Nephi foretell of the restoration of the Jews in the latter days to the Holy Land, 2 Nephi 21–ch. 14 quoting Isaiah 11–ch. 14.

- The Church website says the small plates are a spiritual history. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/triple-index/plates-of-nephi-small?lang=eng. Nephi does say the small plates were made “for the special purpose that there should be an account engraven of the ministry of my people,” 1 Nephi 9:3, but the characterization of these plates as a spiritual history prompts the reader to focus on the events rather than the message carried by the story.

- These figurative forms are absent in 2 Nephi.15 Moreover, Nephi expressly says 1 Nephi is not a history; instead, he says the small plates are for what is “good in [the Lord’s] sight, for the profit of [his] people. . . . that which is pleasing unto God.”162 Nephi 5:30, 32. Nephi’s brother, Jacob, warned the Nephites about their sins and the awful consequences of sin. He said he could not write “a hundredth part of the proceedings of this people . . . upon these plates; but many of their proceedings are written upon the larger plates . . . .” Jacob 3:13.

- Wikipedia s.v. pardes. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pardes_(Jewish_exegesis)

- Neil L. Andersen used this video in a conference talk, “The Eye of Faith” in April 2019. The talk, including the video, is at https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2019/04/25andersen?lang=eng.

- Yoram Hazony, The Philosophy of Hebrew Scriptures (Cambridge, N.Y.: Cambridge University Press, 2012) at 211. (emphasis in original). Hazony presents many biblical examples of the indistinguishability of physical reality and the thought of something in his book. Paul seems to be adverting to this metaphysical reality when he says “all things are naked and opened unto the eyes of [God].” Hebrews 4:13. And the Savior in our day has said that “all things unto me are spiritual . . . . not temporal,” D&C 29:34–35, and that “all things are present before mine eyes,” D&C 38:2.

- Gordon B. Hinckley described the revelatory process he enjoyed as the president, prophet, seer, and revelator of the Church in terms of Elijah’s still-small-voice metaphor, which, of course, is not a voice, He said was not a voice; rather, it was the consensus of thought native to him and his counselors, not a voice. When asked what revelation was, “how that works. How . . . you receive divine revelation,” he said, “Now, if a problem should arise on which we [the leadership of the Church] don’t have an answer, we pray about it, we may fast about it, and it comes. Quietly. Usually no voice of any kind, but just a perception in the mind. I liken it to Elijah’s experience.” Don Lattin, “Musings of the Main Man,” San Francisco Chronicle (April 13, 1997). http://www.sfgate.com/news/article/SUNDAY-INTERVIEW-Musings-of-the-Main-Mormon-2846138.php.

Gordon B. Hinckley was asked the same question by an Australian television interviewer, and he gave the same answer, using the still-small-voice metaphor but not explaining it. He said,

Now we don’t need a lot for continuing revelation. We have a great, basic reservoir of revelation. But if a problem arises, as it does occasionally, a vexatious thing with which we have to deal, we go to the Lord in prayer. We discuss it as a First Presidency and as a Council of the Twelve Apostles. We pray about it and then comes the whisperings of a still small voice. And we know the direction we should proceed. . . . This is revelation. . . . I feel satisfied that in some circumstances we’ve had such a revelation.

“Compass” interview (ABC News) with President Gordon B. Hinckley conducted by David Ranson. Aired November 9, 1997. http://www.abc.net.au/compass/intervs/hinckley.htm (accessed February 3, 2016)(“Compass” is an ABC TV program in Australia that explores faith, belief and values in Australia and around the world.).

- This Western separation of the idea of something from the thing itself caused the ancient Greeks, to whom we owe this philosophical distinction because of Aristotle, to opine that the most perfect part of the thing was the idea of it, not its reality. In fact, the word metaphysics is the Latin form of the Greek τα μετα τα φυσικα, which literally translates as the beyond the physical. The Greek word μετα transliterates to meta, which is the source of many English words like metamorphosis and metadata, this latter word describing the computer data behind what is seen on the computer screen or the flat, two-dimensional printout of a document that just lacks the depth of information present with the document before it is printed. The law describes documents created on a computer, emails and contracts, for example, as electronically stored information or ESI. When a lawyer involved in litigation produces a document for the other side to inspect, the metadata must be produced with the document in its native-file format, because the metadata is a part of the document and producing the document without that data is not allowed. See, e.g., Lake v. City of Phoenix, 222 Ariz. 547, 550–551 ¶13 (2009). Metamorphosis is analogous to the process a reader must have when reading the scriptures: the reader must appreciate what happens to the literal words by metamorphosing the words on the page to the meaning intended by the writer, like the metamorphosis of the caterpillar to the butterfly. This meaning behind the words is the reason for the word metaphor.

- 1 Nephi 1 (bolding added).

- 1 Nephi 1:6.

- An anecdote about DeMille’s pillar of fire underscores the problem associated with DeMille’s and Arnold Friberg’s literal portrayal. The author was at lunch with Josh Jones, an eighteen-year-old full-time missionary from Northern Minnesota, on Monday, November 25, 2019, talking about the meaning of the pillar-of-fire metaphor. Elder Jones, on his mission for about one month, confessed that he had always wondered how a pillar of fire could stop the armies of Pharaoh. After all, he supposed it would have been an easy thing for the Pharaoh’s armies to simply go around the pillar. It had never occurred to him that the pillar of fire was a metaphor for the thing that stopped Pharaoh, just as it is a metaphor in the description of Lehi’s prayer. Elder Jones is now focused on the meaning of the metaphor’s tenor rather than visualizing and making the metaphor’s vehicle a literal event.

- As observed in an early blog posting, https://studyitout.com/operations-of-the-spirit-part-8-other-modern-day-revelations-dc-11-50/ the Lord had to give repeated revelations to the early members of the Church in this dispensation to disabuse them of their propensity to put a supernatural gloss on revelation and the workings of the Spirit. Apparently, people are not reading or understanding the Doctrine and Covenants.

- Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged, s.v. dwell, accessed November 27, 2019, http://unabridged.merriam-webster.com.

- 1 Nephi 1:6.

- One example underscores how easily the writer’s meaning can be lost. Herman Melville names the ill-fated ship in Moby Dick the Pequod. There was an Indian tribe name Pequot that was virtually annihilated in what was the first American conflict with Native Americans in the late 17th Century. Melville’s naming of the whaling ship that would be destroyed in his novel is presaged to the astute reader by the name of the ship. This example is taken from William Harmon and C. Hugh Holman, A Handbook to Literature, seventh ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc., 1996) s.v. metaphor.

“Actually hearing a voice and thinking about a voice are the same from the Hebrew perspective” brought to mind the list of spiritual gifts in Doctrine and Covenants 46. While I’ve never thought there was a hierarchy of these spiritual gifts, you made me think whether some of the gifts were actually the same gift, for example “19 And again, to some it is given to have faith to be healed; 20 And to others it is given to have faith to heal.”