Operations of the Spirit: Part 9(a) Isaiah 11

This is the first subpart or the ninth of fifteen parts to an

essay entitled "Operations of the Spirit"; this part covers

Isaiah 11. The entire essay is just over one hundred pages

if printed out, so it is presented serially in this blog. These

parts should be read sequentially, because each builds on the

previous parts. Hopefully, readers will have comments, suggestions

and criticisms. The fifteen parts are as follows:

I. Introduction, Part I

II. Confusing Terms, Part II

III. Metaphors and Meaning, Parts III through VI

A. The still small voice, Part III

B. The heart and reins, Part IV

C. Light and burning, as in a burning in the bosom, Part V

D. Extracting meaning from metaphors,, Part VI

IV. The Scriptures and the Spirit, Parts VII through X

A. The Oliver Cowdery revelations: D&C 6, 8 and 9, Parts VII(a), (b), and (c)

B. Other modern-day scriptures, Part VIII

C. Ancient scriptures about the Spirit, Part IX

D. Extraordinary events, Part X

V. The Spirit and Individual Affectations, Part XI

VI. Conclusion, Part XII

There are footnotes in this work. You can read the footnotes

by hovering your cursor over the note, or you can click

on the note to read it as text. There is a symbol at the end

of each footnote that allows you to return to the text

by clicking on it.

XI. ANCIENT SCRIPTURES ABOUT THE SPIRIT

There are many ancient scriptures that address the Holy Ghost and the office of Holy Ghost. For purposes of this essay, however, three will do. The first is Isaiah 11. The second is Nephi’s discussion of he Spirit in 2 Nephi 31–ch. 32. The third is the first nine chapters of Proverbs. Each of these will be considered as subparts of this section of this blog on the operations of the spirit.

1. Isaiah 11: Moroni’s Teachings to Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith was instructed on the methods of the Spirit when Moroni1 appeared to tell him about the plates in the Hill Cumorah. Moroni quoted Isaiah 11 to him, which appears word-for-word in the Book of Mormon.2 Joseph Smith does not say what accompanied this quote, an exposition of the scripture. Indeed, Joseph Smith says he did not write the “many explanations” given.3 Isaiah 11 was quoted, and explained to Joseph Smith, so it deserves analysis.

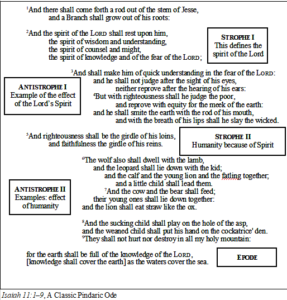

Isaiah 11  is a classic Pindaric ode.4 This type of ode uses repetition of exergasia in strophes and repetition of examples via antistrophes that illustrate the effects of the points made in the two strophes. The stanzas of this ode are preceded by a verse declaring that this scripture is about a man via the rod and branch metaphors.5 The stanzas are followed by an epode summarizing the essence of the stanzas. Parsing this ode provides meaning and, presumptively, the explanation Moroni gave Joseph Smith about the Spirit, which is the focus of the first nine verses. These nine verses confirm the early revelations in this dispensation about the nature of the Spirit.

is a classic Pindaric ode.4 This type of ode uses repetition of exergasia in strophes and repetition of examples via antistrophes that illustrate the effects of the points made in the two strophes. The stanzas of this ode are preceded by a verse declaring that this scripture is about a man via the rod and branch metaphors.5 The stanzas are followed by an epode summarizing the essence of the stanzas. Parsing this ode provides meaning and, presumptively, the explanation Moroni gave Joseph Smith about the Spirit, which is the focus of the first nine verses. These nine verses confirm the early revelations in this dispensation about the nature of the Spirit.

The first strophe is a series of three hendiadyses forming an anaphora.6 These hendiadyses define the spirit of the Lord. The sense to be gathered from each hendiadys is synergistic. The first hendiadys is wisdom and understanding. Not merely wisdom, but wisdom and understanding. In an almost chiastic way, this wisdom and understanding is balanced by knowledge and fear of the Lord, reciprocal definitions of these terms: wisdom involves knowledge and understanding involves fear of the Lord. The wisdom, understanding, knowledge and fear of the Lord bookend the central point of the first strophe, the might that comes from counseling with others or, in other words, sharing one’s knowledge with others to achieve a consensus.

The Spirit as thus defined does not involve an infusion from the Lord’s mind into another’s; rather, the Spirit is tantamount to using one’s own mind.7 Improving one’s mind, in other words, necessarily precedes discipleship and the reception of the Spirit.8 One gains wisdom and understanding—improves one’s mind—through experience, but an experience-only approach limits the breadth of what one can know.9 Likewise, a strictly academic focus ignores natural talents—mental abilities—honed by experience. But learning by one’s own experience, is not enough because it eschews the strengthening counsel of others. Moreover, knowledge10 used for the purposes of the Lord, gleaned from study of the scriptures, is an essential part of this definition of the Spirit.11

One with the Spirit of the Lord, thus, uses his/her knowledge in furtherance of the Lord’s work. The knowledge needed to further the work of the Lord can come through personal study or experience; it can be the result of insight and consensus through counseling with others; in extraordinary, rare circumstances, a one can be told something—hear an actual voice—when particular, immediately needed knowledge is otherwise unavailable.12

Counsel and might is the central point of the first strophe in Isaiah 11 and deserves particular attention. Counsel involves an interchange of ideas among peers: discussion of concepts and opinions.13 Might connotes great mental power and, as a result, commanding influence.14 The hendiadys counsel and might, then, refers to the soundness of collection conclusions and perspectives. The importance of consensus or collective action when it comes to following the Spirit cannot be overstated.15

Spiritual experiences are not, using the definition of Isaiah 11, dramatic experiences. Spiritual experiences are akin to normal interaction and exchange of information. The scriptures that talk about being told something by the Spirit clearly do not ordinarily involve actually hearing a voice so much as reasoning through something in one’s mind.16 It may well be that hearing, as used in the scriptures, is not an auditory experience because the Hebrew weltanshauung does not differentiate between words and objects after the manner of Greek philosophy.17

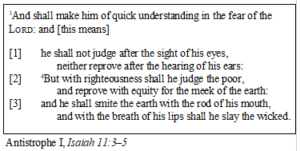

Antistrophe I defines by example what it means “have a quick understanding in the fear of the Lord.” These are examples of what it is to be spiritual are presented by a series of three couplets, which each form an hendiadys: one will be able (1) to see beyond superficial and to sort past the rumors he hears about people, (2) to be equally fair to rich/poor alike and, other words, to reprove the meek fairly, (3) to declaim against wickedness as a spiritual leader should and to use of knowledge and wisdom to “slay the wicked”; the tenor of this slay-the-wicked metaphor is the power of a spiritual individual, which the vehicle intends: rebuffs of the wicked18 and destruction of evil designs.

Antistrophe I defines by example what it means “have a quick understanding in the fear of the Lord.” These are examples of what it is to be spiritual are presented by a series of three couplets, which each form an hendiadys: one will be able (1) to see beyond superficial and to sort past the rumors he hears about people, (2) to be equally fair to rich/poor alike and, other words, to reprove the meek fairly, (3) to declaim against wickedness as a spiritual leader should and to use of knowledge and wisdom to “slay the wicked”; the tenor of this slay-the-wicked metaphor is the power of a spiritual individual, which the vehicle intends: rebuffs of the wicked18 and destruction of evil designs.

The three examples of the effects of spirituality in Isaiah 11:3–5 are a series of three couplets (poetic refrains, exergasias). These couplets use concrete examples to add dimension to the otherwise amorphous nature of general terms at the beginning of this antistrophe, quick understanding and fear of the Lord. These couplets are concentric in the sense that they expand from the individual to the world: the first deals with judgment and reproof of a particular individual; the second deals with judgment and reproof of a class of individuals; and the third deals with the mankind in general. Judgment and reproof of the world are untempered by individual considerations, but the judgment and reproof of classes of people and then individuals are progressively more focused and less affected by the general rule.19 A spiritual person will have these characteristics while one without the spirit will not. This is something of a litmus test, in other words, that enables others to know if a person is spiritual or not, and part of this spirituality is, perhaps, being more generous, patient, and forgiving with individuals than groups.scientist

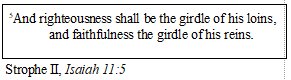

Strophe II, Isaiah 11:5, is a couplet. It shifts gears because it turns to the compassion of this imbued-with-the-spirit person. The seat of compassion during the bible era, which includes the Book of Mormon, was the kidneys.20 The kidneys, usually translated as loins, reins, or bowels (as in the bowels of compassion), is the metaphor or vehicle alluding to empathy and emotion. This empathetic response, however, is bounded by righteousness and faithfulness when it involves a Spiritual experience—righteousness and faithfulness are used interchangeably in this couplet.. Thus, unrighteous sorrow or empathy or anger, like weeping for the criminal who is caught or being angry that one is caught, is not consistent with the Spirit of the Lord.

Strophe II, Isaiah 11:5, is a couplet. It shifts gears because it turns to the compassion of this imbued-with-the-spirit person. The seat of compassion during the bible era, which includes the Book of Mormon, was the kidneys.20 The kidneys, usually translated as loins, reins, or bowels (as in the bowels of compassion), is the metaphor or vehicle alluding to empathy and emotion. This empathetic response, however, is bounded by righteousness and faithfulness when it involves a Spiritual experience—righteousness and faithfulness are used interchangeably in this couplet.. Thus, unrighteous sorrow or empathy or anger, like weeping for the criminal who is caught or being angry that one is caught, is not consistent with the Spirit of the Lord.

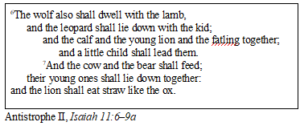

The limitations of righteousness and faithfulness are made concrete by the examples in antistrophe II, which give examples that explain the loins/reins exergasia in strophe II in concrete terms. The essential response of an individual to the Spirit of the Lord is analogous to the interaction one has with a little child; hence, the center of the chiasmus used in this second antistrophe is being led by this little child.21 On either side of this analogy are metaphors for various individuals with different personality types who, invariably, have different interests, attention spans, and patience with certain types of views;22 nonetheless, the Spirit of the Lord allows these people to be together as friends: dwelling together, socializing, sleeping in company, and eating together. The spirit of the Lord, thus, invites the healthy discussion in a high priest group meeting or gospel doctrine class on topics, and the individual who gets angry or accusatory or feels threatened lacks the girdle that should hold his passions in check.

The limitations of righteousness and faithfulness are made concrete by the examples in antistrophe II, which give examples that explain the loins/reins exergasia in strophe II in concrete terms. The essential response of an individual to the Spirit of the Lord is analogous to the interaction one has with a little child; hence, the center of the chiasmus used in this second antistrophe is being led by this little child.21 On either side of this analogy are metaphors for various individuals with different personality types who, invariably, have different interests, attention spans, and patience with certain types of views;22 nonetheless, the Spirit of the Lord allows these people to be together as friends: dwelling together, socializing, sleeping in company, and eating together. The spirit of the Lord, thus, invites the healthy discussion in a high priest group meeting or gospel doctrine class on topics, and the individual who gets angry or accusatory or feels threatened lacks the girdle that should hold his passions in check.

The epode concludes with the knowledge of the Lord filling and covering the earth. The punctuation does not help the presentation, and the understood subject and predicate of the second sentence are required to complete this couplet, but the sense is a clear repetition of the first strophe/antistrophe. Knowledge of the Lord must mean the knowledge that the Lord has, not knowledge that the Lord is real.23 Knowledge by study and experience, in other words, is the essence of the spirit of the Lord, but that knowledge, obviously, can and will be supplemented in those rare instances when some bit of knowledge is needed immediately, and this need will result in the dramatic experience of the voice or infusion of the needed knowledge from outside the individual.

The epode concludes with the knowledge of the Lord filling and covering the earth. The punctuation does not help the presentation, and the understood subject and predicate of the second sentence are required to complete this couplet, but the sense is a clear repetition of the first strophe/antistrophe. Knowledge of the Lord must mean the knowledge that the Lord has, not knowledge that the Lord is real.23 Knowledge by study and experience, in other words, is the essence of the spirit of the Lord, but that knowledge, obviously, can and will be supplemented in those rare instances when some bit of knowledge is needed immediately, and this need will result in the dramatic experience of the voice or infusion of the needed knowledge from outside the individual.

The extraordinary manifestations of the Spirit are discussed in Part X of this blog. Suffice it to say here that most revelations are the result of connecting the dots of information in one’s head, not the sort of supernatural experience D&C 50 warns against as discussed in Part VIII of this blog. For example, Lehi knew what was happening in Jerusalem before he fled for his life with his family. His revelatory prayer is described with metaphors, “there came a pillar of fire and dwelt upon a rock before him.”24 These vehicles are metaphors Nephi used and do not describe literal events. Metaphors are vehicles for what really happened or what is to be learned, the tenor of the metaphor. What really happened as Lehi prayed will be the subject of a future blog, but suffice it to say here that Lehi had enough insight into the goings-on in Jerusalem at the time that his conclusion that he had to flee or die was patent. Lehi did not have top be a rocket scientist—to use a metaphor—to figure out that—forgive this additional metaphor—he had to get out of Dodge or die. Unfortunately, the lesson taught by D&C 50 is not understood by many or most members of the Church who still look for some supernatural manifestation—like a caloric burning in the bosom or frisson—attending revelation. Obviously, those who produced the 2019 video series on the Book of Mormon did not understand how revelation is received, because the Church video published September 20, 2019, is misleading insofar as the revelation Lehi had about getting killed or leaving Jerusalem: Lehi’s prayer is portrayed in the supernatural terms the Doctrine and Covenants says are not true.25

How the BYU motion picture studio wrongly portrays Lehi’s prayer can be seen here:

Likewise, the motion picture studio made Lehi’s dream a supernatural experience; the portion of the video portraying Lehi on his bed can be seen here:

The video continues with this supernatural, dramatic presentation of Nephi’s prayer and resulting confirmation that his father was right, which, again, is inconsistent with the how of spiritual confirmation.

Nephi’s experience can be viewed here:

What is unfortunate about this portrayal is that it give the impression, particularly to young minds, that this is the sort of experience one should expect in answer to prayer. It is poppycock.

Endnotes

- Common opinion says it was Moroni who appeared to Joseph Smith to tell him about the plates, not Nephi. The 1838 manuscript history dictated by Joseph Smith, which was printed in 1842 and 1852, says it was Nephi, as did Lucy Mack Smith, Joseph Smith’s mother, and Mary Whitmer, David Whitmer’s mother. See Brant A. Gardner, The Gift and Power, Translating the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2011) at 92 n. 7. It would make more sense if it was actually Nephi who appeared because of the extended discussions of Old Testament scriptures, discussed infra, because Nephi would have been more familiar with the stylistic elements of Isaiah, which, as will be seen, are essential to appreciating what is at work in the quoted Isaiah scripture.

- 2 Nephi 21.

- JSH 1:36–41. This series of verses includes, “After telling me these things, he commenced quoting prophecies of the Old Testament. . . . though with a little variation . . . . he quoted it thus . . . . he quoted it thus . . . . He also quoted the next verse differently . . . . he quoted the eleventh chapter of Isaiah, saying it was about to be fulfilled He quoted the third chapter of Acts . . . precisely . . . . He said that that prophet was Christ [that the day mentioned] soon would come. He also quoted . . . Joel . . . said that this was not yet fulfilled, but was soon to be. And he further stated . . . . He quoted many other passages of scripture, and offered many explanations which cannot be mentioned here.” The fact that Joseph Smith knew he had been quoted scripture “with a little variation . . . . differently . . . .precisely” and that the reappearance of Moroni resulted in the same instruction “without the least variation,” Id. at v. 41, means one of two things. Either Joseph Smith’s mind and memory were such that he deduced the variances or not in the scriptures quoted and the precise repetition of instruction or he was told about the variations in the scriptures and that he was being instructed with the instructions repeated exactly. More than likely, it was Joseph Smith’s eidetic memory, discussed in Part VIII9a) of this blog, that explains his ability to remember with such precision.

- An ode is a single, unified strain of exalted lyrical verse directed at a single purpose and dealing with one theme. The Pindaric ode is characterized by three strophes where two strophes and antistrophes are alike in form and the concluding epode is different. This was originally a Greek form of dramatic presentation that was sung with the chorus of singers moving up the stage in one direction during the strophe and down the stage during the antistrophe and then stood in place during the epode. Harmon, William and Holman, C. Hugh, A Handbook to Literature,7th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ, Prentice Hall, 1996) s.v .ode.

- Metonymy—the substitution of the name of an object closely associated with a word or person for the word or person—is a type of metaphor, a literary device used throughout the scriptures. Rod is consistently used in the Old Testament in this manner. See, e.g., Psalms 23, Isaiah 10:5, 15; 11:1; 14:29. Jeremiah 1:11, 10:16, 48:17 and 51:19. The New Testament and the Book of Mormon, likewise, use rod as a metonym for leadership. Revelation 2:27; 12:5; 19:15; 1 Nephi 8:24, 30, 11:25, 15:23; 2 Nephi 19:4 (paraphrasing Isaiah 9); 2 Nephi 21:1, 4 (paraphrasing Isaiah 11); 2 Nephi 24:29 (paraphrasing Isaiah 14). Simply put, rod was used to refer to leadership or the leader because the rod or staff was such an incident of leadership that it could not be separated from this office in much the same way a king’s scepter or crown is associated with his regal role. Trees are made up of sticks or rods and represent a people. There is not room in this blog to explicate fully these figures of speech, which, when properly understood, have a dramatic effect on the interpretation, for example, of Lehi’s and Nephi’s visions of the tree of life.

- An anaphora is a devices of repetition typical of the Old Testament. For example, Deuteronomy 28:2–6 (those who hearken to the voice of the Lord shall be blessed); Psalms 3 (The Lord is the protector and salvation for David and the Lord’s people); Isaiah 51:1–9 (hearken to the Lord, He is near, lift up eyes to heaven, hearken, awake and put on strength); Jeremiah 4:23–26 (I beheld repeated at the beginning of each verse).

- This is the essence of the explanation to Oliver Cowdery. Indeed, the Lord commanded the early saints to teach one another the doctrine of the kingdom, which He then describes as the knowledge of things one learns in school:

Teach ye diligently and my grace shall attend you, that you may be instructed more perfectly in theory, in principle, in doctrine, in the law of the gospel, in all things that pertain unto the kingdom of God, that are expedient for you to understand; 79Of things both in heaven and in the earth, and under the earth; things which have been, things which are, things which must shortly come to pass; things which are at home, things which are abroad; the wars and the perplexities of the nations, and the judgments which are on the land; and a knowledge also of countries and of kingdoms— 80That ye may be prepared in all things when I shall send you again to magnify the calling whereunto I have called you, and the mission with which I have commissioned you.

. . . .

And as all have not faith, seek ye diligently and teach one another words of wisdom; yea, seek ye out of the best books words of wisdom; seek learning, even by study and also by faith.

. . . .

Appoint among yourselves a teacher, and let not all be spokesmen at once; but let one speak at a time and let all listen unto his sayings, that when all have spoken that all may be edified of all, and that every man may have an equal privilege.

- Converts in the early days of the church were baptized before they were instructed in the doctrines of the kingdom, but they had to be taught “all things concerning the church of Christ to their understanding, previous to their partaking of the sacrament and being confirmed by the laying on of hands.” D&C 20:68. Obviously, then, modern-day baptism, unlike the different ordinance before Christ, does not involve a covenant, but taking the sacrament does; indeed, the covenant is expressed in the prayer. An article in BYU Studies conflates pre- and post-Christian baptisms while ignoring the new ordinance, the sacrament, adopted after the resurrection Reynolds, Noel B. “Understanding Christian Baptism through the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies, vol.51, no. 2 (2012) at 5 et seq.

- Benjamin Franklin is reputed to have said, “Experience keeps a dear school, but fools will learn in no other.”

- Knowledge is described as the summum bonum of the priesthood in D&C 128:11–14, “This, therefore, is the sealing and binding power, and, in one sense of the word, the keys of the kingdom, which consist in the key of knowledge.” The nature of the priesthood is, again, beyond the scope of this paper, but it is worth noting that everyone has their own priesthood power if the exercise of knowledge is what priesthood is. This explains why there are different orders of the priesthood, like the one after the holy order of the Son of God, which must be different than the priesthood exercised by the Father or even women or, for that matter, the priesthood exercised by the Adversary. However, the performance of certain ordinances for salvation would require the delegated authority of the Lord’s priesthood, the Melchizedek priesthood.

- The central point of the chiasmus about Joshua’s calling is an injunction that he study the scriptures daily, Joshua 1:8. Books were delivered to Ezekiel, Ezekiel 2:8–3:3; Lehi was “filled with the Spirit of the Lord” (which means, perhaps, that he gained knowledge and insight) when he read the book delivered to him, 1 Nephi 1:8–13; and John the Revelator had a book delivered to him, Revelation 10. Hyrum Smith, as discussed above, was told, “Seek not for riches but for wisdom; and, behold, the mysteries of God shall be unfolded . . . . Seek not to declare my word, but first seek to obtain my word, and then shall your tongue be loosed . . . you shall have my Spirit.” D&C 11:7, 21. The saints were commanded to “seek ye diligently and teach one another words of wisdom; yea, seek ye out of the best books words of wisdom; seek learning, even by study and also by faith [i.e., experience].” D&C 88:118. This injunction was followed by a commandment to establish a “house of learning,” D&C 88:119, where there would be a teacher, D&C 88:122, a “school [for] the prophets,” D&C 88:127. The Lord even commanded that the study should be about science, history, politics, and nations. D&C 88:78–79. The commandment to seek learning by study and experience was repeated in the dedicatory prayer to the Kirtland temple:

And as all have not faith, seek ye diligently and teach one another words of wisdom; yea, seek ye out of the best books words of wisdom, seek learning even by study and also by faith; Organize yourselves; prepare every needful thing, and establish a house, even a house of prayer, a house of fasting, a house of faith, a house of learning, a house of glory, a house of order, a house of God . . . And do thou grant, Holy Father, that all those who shall worship in this house may be taught words of wisdom out of the best books, and that they may seek learning even by study, and also by faith, as thou hast said . . . .

- An actual voice can happen, but it is rare. Moreover, those who have these experiences are admonished not to speak freely about it, “And when we have a great and exceptional experience, we rarely speak of it publicly because we are instructed not to do so (see D&C 63:64) and because we understand that the channels of revelation will be closed if we show these things before the world.” Dallin H. Oakes, “In His Own Time, in His Own Way,” Ensign (August 2013)(from an address to new mission presidents on June 27, 2001).The scripture cited in this quote is: “Remember that that which cometh from above is sacred, and must be spoken with care, and by constraint of the Spirit through prayer, wherefore, with this there remaineth condemnation.”

- The first definition of counsel in the Oxford English Dictionary is:

Interchange of opinions on a matter of procedure; consultation, deliberation. to take counsel: to consult, deliberate.

Oxford English Dictionary, 2d ed. on CD-ROM (v. 4.0)(New York: Oxford University Press, 2009) s.v. counsel.

- Id. s.v. might. Might can, also, refer to physical power, but the context in this scripture excludes this possibility.

- The co-equal authority of the Quorum of the First Presidency, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and the Seventy is dependent upon “the unanimous voice of the same; that is, every member in each quorum must be agreed to its decisions, in order to make their decisions of the same power or validity one with another.” D&C107:27.

The only exception to the requirement of unanimity appears to be in church disciplinary proceedings where, at least originally, it was stated that “the majority of the council [has] power to determine the [case]” D&C 102:22. The practice in the church today does not usually involve anything other than a sustaining vote, rather than a vote by of individual opinion, so the majority-controls rule does not come into play, and those who preside at church disciplinary proceedings think they are the ones to make the decision without getting a unanimous consensus; they merely call for a sustaining vote.

The requirement of a consensus decision has affected major decisions in the church. Banning blacks from the priesthood is an example. The biography of David O. McKay, Prince, Gregory A. and Wright, William Robert, David O. Mckay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism (Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press, 2005), makes it clear that President McKay’s desire to end the priesthood ban was impossible given the opinions of the general authorities during his tenure as president. The consensus of opinions was not shared by President McKay who wrote the following when Harold B. Lee and Joseph Fielding Smith were pressing for the excommunication of Sterling M. McMurrin in March 1954 because McMurrin was urging a change to eliminate the priesthood ban:

There is not now, and there never has been a doctrine of this Church that the Negro are under a divine Curse. . . . We believe . . . that we have scriptural precedent for withholding the priesthood from the Negro. It is a practice, not a doctrine, and the practice will some day be changed. And that’s all there is to it.

Id.at 79–80 (emphasis in original).

It was not until December 5, 2013 (this date is based on an article published in the Salt Lake Tribune by Peggy Fletcher Stack on December 9, 2013, “Mormon church traces black priesthood ban to Brigham Young,” http://www.sltrib.com/sltrib/news/57241071-78/church-lds-says-mormon.html.csp), that the Church first acknowledged the source of the priesthood ban with a posting on http://www.lds.org/topics/race-and-the-priesthood saying it was Brigham Young:

In 1850, the U.S. Congress created Utah Territory, and the U.S. president appointed Brigham Young to the position of territorial governor. Southerners who had converted to the Church and migrated to Utah with their slaves raised the question of slavery’s legal status in the territory. In two speeches delivered before the Utah territorial legislature in January and February 1852, Brigham Young announced a policy restricting men of black African descent from priesthood ordination. At the same time, President Young said that at some future day, black Church members would “have [all] the privilege and more” enjoyed by other members.

This same posting on the LDS website underscores that social milieu at the time of Brigham Young’s political speeches before the territorial legislature on January 23 and February 5, 1852, and “disavows the theories advanced in the past that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor . . . actions in a premortal life; that mixed-race marriages are a sin; or that blacks . . . are inferior in any way to anyone else.” Brigham Young’s speeches, like many others of early Church leaders were taken down in Pitman shorthand but not transcribed until Lajean Purcell Carruth taught herself how to read the shorthand notes sometime before 2013 according to an article, “Lost Sermons,” written by Matthew S. McBride that was published in the Ensign (Dec. 2013).

The characterization of Brigham Young’s speech to the Utah legislature on February 5, 1852, is kind. The speech can be read at https://dcms.lds.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE2343307. Ronald K. Esplin wrote a paper about the blacks and the priesthood in 1979 while he was a Ph.D. candidate at BYU and a research historian at the Historical Department of the Church. Esplin did not have the transcription of Young’s remarks because they had not yet been transcribed. His paper can be read at https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol19/iss3/12. Esplin makes a strong argument that the exclusion of blacks from the priesthood was an accepted fact long before Brigham Young’s speech before the Utah legislature in 1852.

Esplin did not believe there was a January 1852 speech as referenced in the Church’s websitse when he wrote his paper, but there is. It can be read in Van Wagoner, Richard S., ed. The Complete Discourses of Brigham Young, vol. 1 (Salt Lake City: the Smith-Pettit Foundation, 2009) at 1852–1853. The occasion was a speech by Brigham Young about a proposed bill, An Act in relation to African Slavery.” He said, inter alia, “This colored race have been subjected to severe curses, which they have in their families and their classes and in their various capacities brought upon themselves. . . . I am a firm believer in Slavery. . . . I am firm in the belief that they ought to dwell in servitude” Id. The original notes of this speech can be seen at https://dcms.lds.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE2343323

- E.g. Nephi’s killing of Laban, 1 Nephi 4:3–18. Nephi leaves his unwilling brothers outside the walls of the city while he, verse six, “was led by the Spirit, not knowing beforehand the things which I should do.” Put another way, Nephi knew he had to get the plates, so he returned to get them, but he did not have a plan. He happens upon Laban in verses seven through eight, examining Laban’s sword a considerable length of time, even taking its heft as he examines it. It occurs to Nephi that he ought to kill Laban with his sword. Nephi characterizes this thought as being “constrained by the Spirit.” 1 Nephi 4:10. But this thought is abhorrent to Nephi, so he wrestles with the idea. Id. Nephi says he “said in my heart,” that he had never killed anyone before; heart being a Hebrew metaphor for the mind. See Part IV of this blog. So Nephi thinks about it some more, realizing that Laban, who was wicked and sought to kill Nephi and is brothers and take their property, has been delivered into his hands, verse eleven. Nephi again thinks about it, verse twelve, because Laban is there, Nephi has Laban’s sword in his hand, and Nephi rehearses in his mind the need for the records, “the Lord slayeth the wicked to bring forth his righteous purposes. It is better that one man should perish than that a nation should dwindle and perish in unbelief.” Nephi then considers the reality that his people would not be able to keep the commandments unless they had them, that the commandments were on the plates Laban had, that Laban was there before him, so he killed him. This experience is ratiocinative.

Revelation is mostly this type of rational process. Another example is Jeremiah’s calling. The Lord does not tell Jeremiah what is going to happen. He asks him what he sees is going to happen and compliments him on seeing well.

Moreover the word of the Lord came unto me, saying, Jeremiah, what seest thou? And I said, I see a rod of an almond tree. Then said the Lord unto me, Thou hast well seen: for I will hasten my word to perform it. And the word of the Lord came unto me the second time, saying, What seest thou? And I said, I see a seething pot; and the face thereof is toward the north. Then the Lord said unto me, [Thou seest well:] Out of the north an evil shall break forth upon all the inhabitants of the land.

- See Hazony, Yoram, The Philosophy of Hebrew Scripture (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012) at 206–211. Greek philosophy distinguishes between the reality of ideas and objects, but the philosophy of the bible does not draw this distinction. Rather, a word is inseparable from the object brought to mind by the word; the word is the thing, itself, as understood. Thus, hearing involves more than merely hearing because it is understanding, itself, that is the object. Thus, the following phrases reflect understanding and conclusion as a part of Nephi’s ratiocination prior to killing Laban, not actual talking: “And the Spirit said unto me,” 1 Nephi 4:11, 12, which is followed in verse fourteen by “when I, Nephi, had heard these words,” and, then, in verse eighteen, “I did obey the voice of the Spirit.”

- Joseph Smith’s declamations against the jailers at the Liberty jail exemplifies the cower-the-wicked effect of a spiritual man. The account of his silencing of the guards is in Parley P. Pratt’s autobiography, Prat, Parley, P. Autobiography of Parley P. Pratt (Salt Lake City, Deseret Book Co., 1985) at 179-180.

- The two extremes are captured by the interaction of the Savior with the scribes and Pharisees tempting the Lord with the woman caught in adultery. The law said she should be stoned, but the Savior would not apply the general rule to the particular woman before Him. John 8:4-11.

- See the discussion of the heart and kidney metaphor at Part IV of this blog. The heart is the metaphor used for the seat of reason, knowledge and logic in the scriptures. Thus, there is an exergasia at work when a scripture says the Lord will “tell you in your mind and in your heart.” This exergasia or hendiadys emphasizes the need for reason and logic, not feelings.

- What it is to be like a little child is beyond the scope of this essay. Suffice it to say here that a little child is not close-minded or, using the metaphor of the scriptures, hard hearted, the heart being the metaphor in the scriptures for the mind.

- Using animal metaphors is common in the scriptures. For instance, wicked lies in wait like a lion, Psalm 10, 17; sheep and the good shepherd, Psalm 23; “So foolish was I, and ignorant: I was as a beast before thee,” Psalm 73:22; “Woe be unto the pastors that destroy and scatter the sheep of my pasture,” “As a roaring lion, and a ranging bear; so is a wicked ruler over the poor people,: Proverbs 28:15; Jeremiah 23:1; Pharaoh is the great dragon, Ezekiel 29:3; every fowl and beast to gather for the Lord’s supper, Ezekiel 39:17; sheep scattered and became meat for beasts of the field because they had no shepherd, Ezekiel 34:5–23; Savior has compassion on people “as sheep having no shepherd,” Matthew 9:36; apostles, as sheep among wolves, are to be wise as serpents and harmless as doves, Matthew 10:16; Savior to divide His sheep from the goats, Matthew 25:32-33; Savior compares himself to the good shepherd, John 10:1–27 Lord gathers his children/sheep from the four quarters of the earth, 1 Nephi 22:25; men like a wild flock that flees from the shepherd, Mosiah 8:21; the Lord is the one who said he had other sheep not of this fold, D&C 10:59–60.

- Knowledge of God is used in the Doctrine & Covenants as a reference to God’s knowledge when addressing the keys to the mysteries of the kingdom, “And this greater priesthood administereth the gospel and holdeth the key of the mysteries of the kingdom, even the key of the knowledge of God.” D&C 84:19. Knowledge of appears twenty-seven times in the Doctrine & Covenants, eighty-seven times in the Book of Mormon, twenty-two times in the Old Testament, and twenty-three times in the New Testament. Jeremiah can be viewed as a philosophical treatise on the nature of truth or knowledge of reality. Hazony, Yoram, The Philosophy of Hebrew Scripture, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012) at 161 et seq. The emphasis on the importance of knowledge found in the Book of Mormon is consistent with knowledge being the essence of priesthood power. See D&C 128:11–14 (Knowledge is described as the summum bonum of the priesthood: so everyone has their own priesthood power if the exercise of knowledge is what priesthood is). Cf. Alma 47:36 (dissenters had same instruction/information as Nephites).

- 1 Nephi 1:5–6

- See Parts VII and VIII of this blog.

I for one have never received revelation as portrayed in the clips above. But I’ve only been a member of the Church for 42 years. It could still happen… ?!

Like many, I watched the first release of the Book of Mormon movie last weekend. I was surprised by a couple things. First, everyone clearly speaks English, while I thought they might limit what the actors actually said to simplify translation into the many languages they will certainly voice over. Second, I was surprised at how much was ‘added’, such as the daily interactions, likely in the interest of movie making. I was expecting something that followed the scriptures much more rigidly, but perhaps that wouldn’t make a good movie. Maybe that’s the reason I don’t direct movies for a living.

It will be interesting to see how these movies will change the way members of the Church study and reflect on the scriptures. My twenty-something children prefer watching a movie over reading a book, so if these movies (realistically) replace scripture reading, I wonder how much will be lost. I have adult members of my ward who fondly recall the Animated Book of Mormon movies, and certainly base some of their mental imagery of the Book of Mormon on those cartoons. I wonder what the broader impact of these movies will be?

(Aside: why is Nephi always portrayed as clean-shaven, while his brothers aren’t? Are the ‘good guys’ supposed to be clean shaven – as in BYU standards – while the bad guys have beards? This drives me crazy…)

That’s it for now. I need to get back to ministering to the many people I know who will never receive revelation by seeing a pillar of light or light-filled room, yet regularly see this imagery. Maybe that’s the difference between a prophet and a regular Joe. In my ministering, I guarantee I will be using this line: “most revelations are the result of connecting the dots of information in one’s head, not the sort of supernatural experience.”

Thanks, Daryl!

You make great points. These movies will, indeed, affect how members study the Book of Mormon. And it is likely to have a negative impact. Readers will have the images in the video in their head–their minds will be set–when they read what Nephi wrote. The movie is a narrative. It tells a story. It does not address the metaphors and other figures of speech that infuse meaning into the message Nephi intended by the events he chose for 1 Nephi: he was not writing a travelogue, after all.

Here are a few provocative question few members can answer. Why did Nephi write two books? He must have had a purpose, right? What was it? Does the video published by the Church underscore Nephi’s purpose for his first book? Or mask it? The answers to these questions will be the subject of a later blog posting.

Your comment highlights the effect of the video. This blog is about Isaiah 11, not the video. The video was intended to be a demonstration of how the portrayal of Lehi’s and Nephi’s prayers are inconsistent with what Isaiah said. But the video so distracted you from the message of the blog–Isaiah’s definition of the Spirit, its effects, and its humanizing tendency–that you focused on the video.

Who wants to parse and ponder Isaiah when you an watch a movie?