1 Nephi 3–ch. 5

These chapters use the return of Lehi’s four oldest sons to obtain the brass plates from Laban as a dramatic and insightful demonstration of the operation of the Spirit. It took three attempts for Laman, Lemuel, Sam, and Nephi to get the plates, and most readers focus on what happened instead of the message to be learned from the events. So there are two main vehicles and the associated teachings to be considered. First, getting the plates and, second, the killing of Laban.

1 Nephi 3–ch. 5

These chapters describe the return of Lehi’s four oldest sons to obtain the brass plates from Laban. It took three attempts for Laman, Lemuel, Sam, and Nephi to get the plates, Nephi was finally successful after he killed Laban during the third try.1So there are two main topics to be considered. First, getting the plates, and, second, killing Laban.

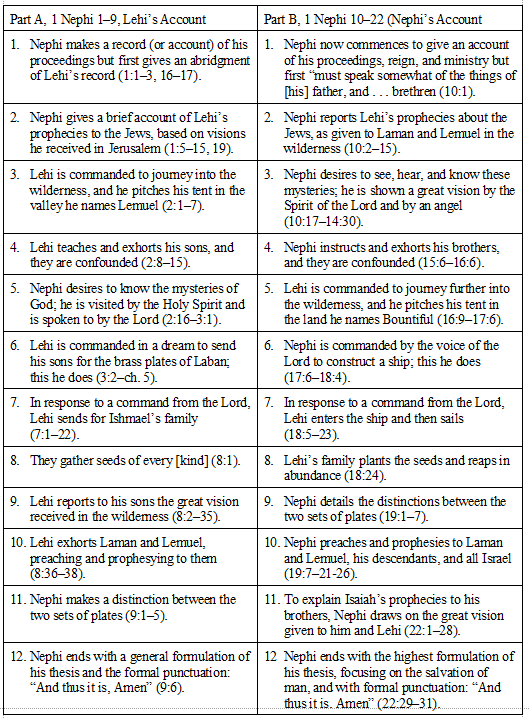

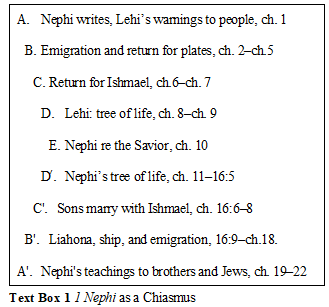

The actual events in these chapters are from Lehi’s record, and are elucidated by the corresponding parts of Nephi’s record. The corresponding parts are item six in the adjoining table: getting the plates and Nephi’s construction of a ship.2Likewise, levels B–Bʹ of the chiasmus outline of 1 Nephi relate the facts or events of the two parallels.

The actual events in these chapters are from Lehi’s record, and are elucidated by the corresponding parts of Nephi’s record. The corresponding parts are item six in the adjoining table: getting the plates and Nephi’s construction of a ship.2Likewise, levels B–Bʹ of the chiasmus outline of 1 Nephi relate the facts or events of the two parallels.

But the parallel facts should not be understood standing alone. The reader must appreciate why they are in the Book of Mormon, and the reader must view the facts from a perspective enhanced by both Nephi’s metaphysical paradigm and his figurative language.

But the parallel facts should not be understood standing alone. The reader must appreciate why they are in the Book of Mormon, and the reader must view the facts from a perspective enhanced by both Nephi’s metaphysical paradigm and his figurative language.

Nephi’s or the Hebrew perspective on reality is, perhaps, the most important key to understanding what Nephi wrote. The metaphysical outlook of the Jews is Nephi’s and makes thinking about words the same as hearing them and thinking about someone the same as seeing that person.3Metaphors and archetypes, likewise, can mislead the reader if the focus is on the vehicle rather than the tenor of these devices.

The literal and simple story in these chapters is superficial: Lehi’s sons return to Jerusalem for the brass plates, encounter problems, and ultimately return with the plates after Laban is killed. But these events are not in 1 Nephi for historical purposes; instead, these events are in Nephi’s record to show how the Spirit works.4It is this message that matters. Moreover, because the vehicle or story is not the important part, it can be changed to fit the message, meaning the facts can be adjusted to convey the message accurately. This is how the Hebrews viewed life and wrote.

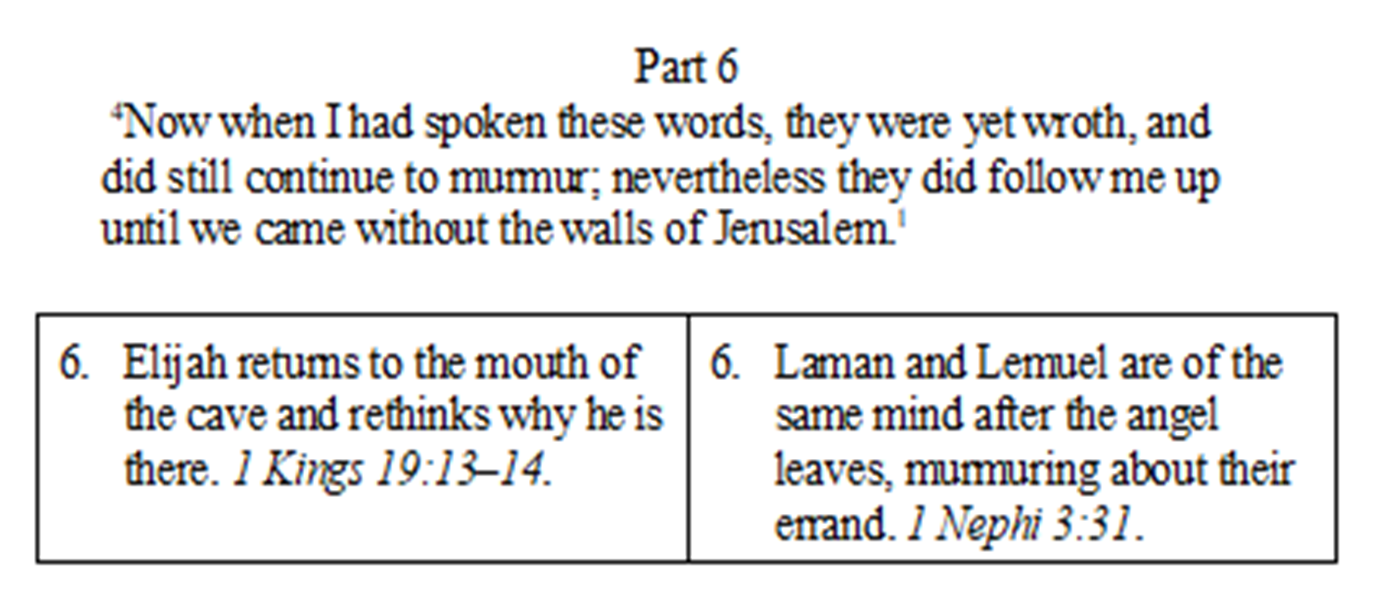

The third attempt to get the plates from Laban is the most informative about the operation of the spirit. Laman and Lemuel were not happy about their situation following the second attempt to get the plates. Laban sent a cohort to kill them, so they hid. Laman and Lemuel began to dress Sam and Nephi down. The reader is advantaged if this story is parsed into seven parts and, when appropriate, reformatted for clarity.5

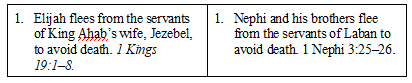

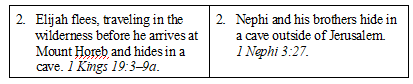

The following seven parts intentionally parallel the obvious correlation between the brothers fleeing for the lives, etc., and Elijah’s flight from Jezebel’s soldiers whom Jezebel sent to kill him. Elijah hid in a cave and had the still-small-voice experience so often referenced today. Nephi’s presentation of the facts as he undertook the third attempt to get the plates alludes Elijah’s experience. The allusion is made explicit in 1 Nephi 17 where the hapax legomenon—still small voice—is actually used.6

Part 17

And it came to pass that we did flee before the servants of Laban, and we were obliged to leave behind our property, and it fell into the hands of Laban.

Part 1 is the introduction to the third attempt. As discussed in conjunction with Nephi’s later review of this experience in 1 Nephi 16–ch. 18. The events described in this introduction parallels Elijah’s flight from Jezebel to escape death.

The parallel or allusion to Elijah’s experience is not obvious without the next part where Nephi explains that he and his brothers hid in the cavity of a rock, something like a cave.

The parallel or allusion to Elijah’s experience is not obvious without the next part where Nephi explains that he and his brothers hid in the cavity of a rock, something like a cave.

Part 28

And it came to pass that we fled into the wilderness, and the servants of Laban did not overtake us, and we hid ourselves in the cavity of a rock.

Elijah traveled in the wilderness for forty days and forty nights—not really, of course, because forty is an anagogic number. He finally took refuge in a cave from those Jezebel sent to slay him.9Lehi’s sons fled from Laban’s servants, but they did not really travel in the wilderness like Elijah. Perhaps, Nephi takes some literary license with the facts so his recounting of events makes the allusion to Elijah’s experience obvious.

Elijah traveled in the wilderness for forty days and forty nights—not really, of course, because forty is an anagogic number. He finally took refuge in a cave from those Jezebel sent to slay him.9Lehi’s sons fled from Laban’s servants, but they did not really travel in the wilderness like Elijah. Perhaps, Nephi takes some literary license with the facts so his recounting of events makes the allusion to Elijah’s experience obvious.

The allusion to Elijah’s experience becomes more compelling because of the flight, the wilderness, and the cave. The third part, also, militates in favor of this parallel. It presents the interchange between the brothers as they hid for their lives in a series of three couplets..

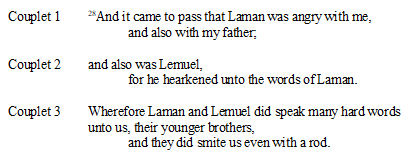

Part 310

Part 3 is a series of three couplets. Each couplet has a qinah-like rhythm typical of a lamentation, so they ought to be read aloud with the voice trailing off as the second half the couplet is read. The second half of each couplet parallels the first half, restating and explaining the first line. The fact that the second half of each couplet repeats what is said in the first half is verified by the fact the first lines of each couplet can be read and make sense without the second half, but the second halves, which are akin to parentheticals, make no sense if they are read without the first part of each couplet.

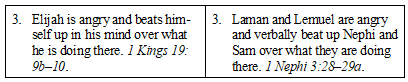

The following table showing the parallel between Elijah’s experience and what Nephi says happened in the cavity of a rock—what most readers think was a physical beating. But, consideration shows it was not a physical beating.

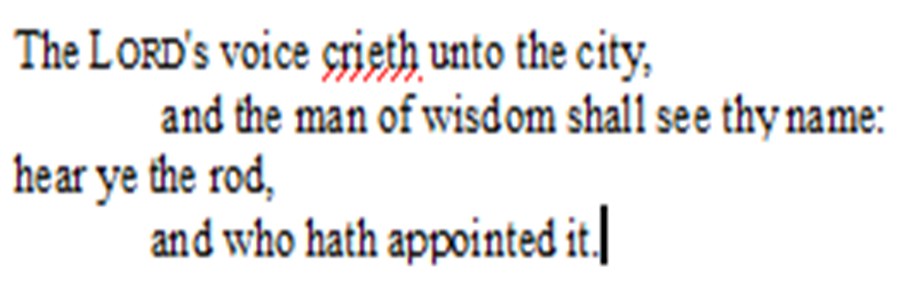

The fact that there was not an actual beating with sticks is difficult for most readers, but analysis is compelling. This third part includes the word rod, a figure of speech. The couplet that uses rod says Laman and Lemuel “did speak many hard words to us.” They were angry with Sam and Nephi; hence, the hard words. In other words, Laman and Lemuel were yelling at Sam and Nephi. The second half of the couplet with the word rod repeats the first half about the hard words Laman and Lemuel were yelling, “they did smite us even with a rod.”

Most readers separate the hard words from the rod-smiting, and most think of the rod in this recitation as a stick of some sort; indeed, the video produced by the Church in 2019 of this rod-smiting is portrayed as a stick-thrashing as pictured in the adjoining artwork and Book of Mormon video produced by the Church.

Perhaps, some think this rod is more like a stick or switch (how it is portrayed in the video, which incorrectly, as will be discussed below, shows an actual angel appearing), but few call it a rod when they talk about their understanding of what they think is a physical beating.11

A physical beating is not likely what Nephi describes because rod, singular, was a such a common metonym for a leader, Laman’s patriarchal right of leadership in this case. Rod is used as a metaphor for Laman’s chastisement of Sam and Nephi. His words as the leader. The rod described by Nephi was as inseparable from leadership during Nephi’s day as the crown of a king or queen is today, “Today the crown announced” or did something. Rod can be a metonym referring to the words of the leader just like one can refer to something the crown says;12for example, Nephi tells Laman and Lemuel that the rod of iron seen in Lehi’s vision of the tree of life represented the word of God,13and the Lord, Himself, has said that people need to repent “lest I smite you by the rod of my mouth.”14

A physical beating is not likely what Nephi describes because rod, singular, was a such a common metonym for a leader, Laman’s patriarchal right of leadership in this case. Rod is used as a metaphor for Laman’s chastisement of Sam and Nephi. His words as the leader. The rod described by Nephi was as inseparable from leadership during Nephi’s day as the crown of a king or queen is today, “Today the crown announced” or did something. Rod can be a metonym referring to the words of the leader just like one can refer to something the crown says;12for example, Nephi tells Laman and Lemuel that the rod of iron seen in Lehi’s vision of the tree of life represented the word of God,13and the Lord, Himself, has said that people need to repent “lest I smite you by the rod of my mouth.”14

Giving the second line of the third couplet the same tenor as the first line, thus, adds a sense otherwise overlooked. Laman and Lemuel were smiting their younger brothers with the rod of Laman’s mouth, Laman declaiming against his presumptuous assumption of leadership. Laman was the rightful leader. So Laman and Lemuel were giving Sam and Nephi a piece of their mind on the subject of who was in charge.

The parallel to Elijah’s revelatory experience is sound so far as this tongue lashing is concerned.15Elijah, likewise, received a tongue lashing, but his dressing down was by his own self-examination, “What doest thou here, Elijah?”16This is followed by Elijah’s rationalization—his life was being sought—the Lord passing by in the various natural phenomenon, and Elijah continued to murmur when the storm had passed.17The still small voice occurs during this post-storm murmuring and rationalization. It is only after Elijah has stopped his murmuring that the word of the Lord tells Elijah to return to from his hiding place and anoint a successor to King Ahab.

Elijah’s revelatory experience, then, includes the berating Elijah gave himself for hiding in the cave and what is characterized as the Lord’s words to Elijah that prompted him to fulfill his prophetic calling.18

The foregoing makes it clear that what happens in Part 3 is a third parallel to Elijah’s experience. The confluence of three parallels justifies the conclusion that Nephi was alluding to Elijah’s experience when he records what happened in the cavity of the rock with his brothers.

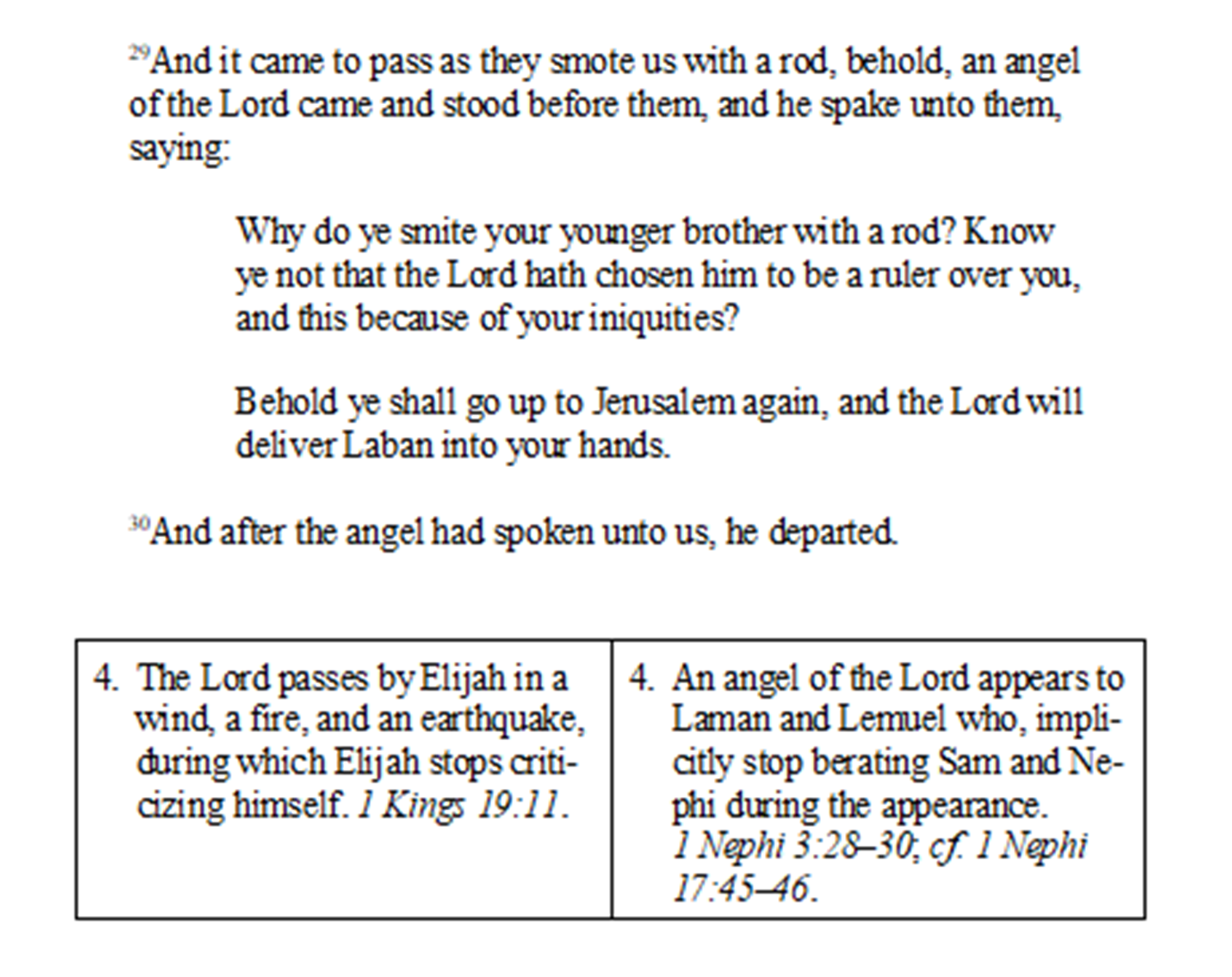

Part 4

Part 4 is the climax of this stylized presentation about returning for the brass plates. It is stylized because the story about the return for the plates follows the traditional literary form common at the time: an introduction, rising action (tying the knot), climax (turning point), falling action (dénouement), and conclusion.19The climax has an angel appear and then departs leaving Laman and Lemuel still complaining, just like Elijah. And the angel in Part 4 chastens Laman and Lemuel for smiting Sam and Nephi with this metonymic rod of leadership, “Why do ye smite your younger brother with a rod? Know ye not that the Lord hath chosen him to be a ruler over you . . .” The only reason to include the query about leadership as something the angel said is if Laman, joined by Lemuel, was berating Sam and Nephi with Laman’s right to lead—smiting them with Laman’s rod of leadership, the rod of his mouth.

This climax is the same climax in the story of Elijah. when the Lord passed by the mouth of a cave, Elijah’s hiding place, in the form of a storm, “[T]he Lord passed by, and in a great and strong wind rent the mountains . . . and after the wind an earthquake . . . and after the earthquake a fire . . . .” 20Elijah still complained to himself after the Lord passed by Elijah, so the continued murmuring by Laman and Lemuel tracks what happened to Elijah. Elijah repeats the same justification for hiding after the Lord-passes-by experience as he used before the experience. Just like Laman and Lemuel: Nephi records that they began to murmur again, meaning they were saying the same thing after the angel’s visit as before.

If Nephi, indeed, intended this story to be an allusion to Elijah’s experience, then the appearance of the angel to Laman and Lemuel should not be read as an angel in propria persona; rather, it parallels the appearance of the Lord in the Elijah experience: the angel appeared in a storm or similar natural phenomenon. The dumbfounding wonder during the appearance–the event–of course, evanecses when the storm has passed, so Laman and Lemuel continued murmuring.

The appearance of the Lord passing by the mouth of Elijah’s cave interrupted the tongue-lashing Elijah was giving himself before the Lord passed by in the wind, earthquake, and fire. But these manifestations of the Lord’s power forces Elijah to realize the power of the Lord—this is where the term still small voice is used—and gets himself together and returns to confront Queen Jezebel, from whom he had fled for his life.

Nephi’s allusion to Elijah’s experience compels the angel that appeared at the cavity in the rock where Laman and Lemuel were berating Sam and Nephi appeared in the form of a mighty storm, this angel interrupting the tongue lashing Laman and Lemuel were giving to their younger brothers. Certainly, the storm caused Elijah to reflect on the power of the Lord and return to confront Jezebel, but the interruption at the cavity in the rock had no effect on Laman and Lemuel—they missed the connection between the power of the Lord that would ensure they got the plates, so they continued to lash out. But Nephi connected the dots in his mind—he saw the storm, the still small voice—and recognized, like Elijah, that he had to try again. So Nephi speaks to his brothers even though they did not connect the dots.

Further elucidation of the angel’s visit to the four brothers hiding outside the walls of Jerusalem is found when Nephi recounts this experience to his older brothers after arriving in the Land of Promise.21Suffice it to say here that the metaphysical paradigm of the Hebrews,22does not militate in favor of concluding that the appearance of the angel to Laman and Lemuel involved an actual person; instead, it is more likely that it was the same as the Lord passing by Elijah at the mouth of the cave where he was hiding from Jezebel’s soldiers.

Elijah was, it seems, impressed with the power of the the Lord when He passed by via the wind, the earthquake, and the fire, but this was not what persuaded Elijah to return and confront Jezebel and the priests of Baal. It was Elijah’s reflections after the storm, what has been translated as a still small voice. The better translation of still small voice would be better presented as Elijah reflections when the only sound was the silence after the storm23

An observation is warranted before turning to Part 5. Part 4, if taken literally, has an angel standing before Laman and Lemuel. But this literal interpretation cannot be. In the first place, this angel would have appeared in Celestial glory—blinding glory—because it would not have been a resurrected being.24Laman and Lemuel would have seen this angel in the angel’s blinding glory, so they would know that Nephi and Sam would have seen the same angel. But there is no indication that Nephi’s brothers, including Sam, saw an angel. The likelihood of even the most wicked person not acknowledging the appearance of an angel appearing in glory is unfathomable.

The Book of Mormon video produced by the Church in 2019 does what it can to deal with the blinding appearance of the angel and the subsequent murmuring by Laman and Lemuel.25Seems almost credible, if one is credulous. Is it really believable that Laman and Lemuel would question what the Lord’s angel had just told them? Moreover, the video portrays Laman and Lemuel as somewhat subdued by the angel’s appearance while, as discussed below, Nephi says “they were yet wroth” after the angel’s appearance.26 The video shows a subdued rather than apoplectic Laman and Lemuel, so the video is not to be believed.

Which leads to the second reason an actual appearance by an angel is unlikely. Nephi later says his older brothers did not believe Nephi ever saw an angel. They believed Nephi lied about seeing an angel to take advantage of them. This observation of his brothers belief occurs just after the death of Ishmael when his older brothers and the Ishmael’s family wants to return to Jerusalem because they did not believe what Nephi and Lehi said about the voice of the Lord and visitation of angels was anything other than what they imagined in their minds.

[T]hey wanted to return again to Jerusalem. And Laman said unto Lemuel and also unto the sons of Ishmael: Behold, let us slay our father, and also our brother Nephi, who has taken it upon him to be our ruler and our teacher, who are his elder brethren.

Now, he says that the Lord has talked with him, and also that angels have ministered unto him. But behold, we know that he lies unto us . . . .

And thou [speaking of Nephi] art like unto our father, led away by the foolish imaginations of his heart; yea, he hath led us out of the land of Jerusalem, and we have wandered in the wilderness for these many years . . .27

There is third reason that militates in favor of the conclusion that an angel was not actually present. Joseph Smith recorded how angels operated anciently, by pointing one’s mind in a particular direction. He records,

God shall give unto you knowledge by his Holy Spirit, yea, by the unspeakable gift of the Holy Ghost, that has not been revealed since the world was until now; Which our forefathers have awaited with anxious expectation to be revealed in the last times, which their minds were pointed to by the angels . . . .28

Finally, an actual appearance by an angel in the angel’s glory taxes credulity by ignoring Nephi’s metaphysical paradigm. Viewing the angel’s appearance from Nephi’s paradigm resolves the paradox of this appearance. Nephi interpreted natural phenomenon as the appearance of an angel the same as Elijah understood the Lord’s appearance in the natural phenomenon at the mouth of his cave. Thus, following the Elijah paradigm, It makes sense that the appearance while Nephi and Sam were being smitten with the rod of Laman and Lemuel’s obstreperousness, was a storm. After all, Laman and Lemuel characterize what Nephi says happened as the foolish imagination of his heart, meaning his mind. But thinking something in the mind is the same as experiencing it in the Hebrew metaphysical paradigm. Laman and Lemuel, apparently, did not connect the interrupting storm with an angelic appearance. But Nephi did, because he was attuned to how the Spirit operates. Laman and Lemuel were not attuned to the operation of the Spirit, so they did not connect the storm that interrupted their rant with the Spirit.

Nephi’s attention to the power of the angel in what was likely a storm leads Nephi to propose another attempt to get the plates. But he had to convince his brothers because they did not understand from what the angel said via the storm that interrupted their harsh words. They just continued to beat Sam and Nephi with the rod of their mouth following the interruption. So Nephi has to convert them to what he perceives is the will of the Lord, and this conversion is found in Part 5.

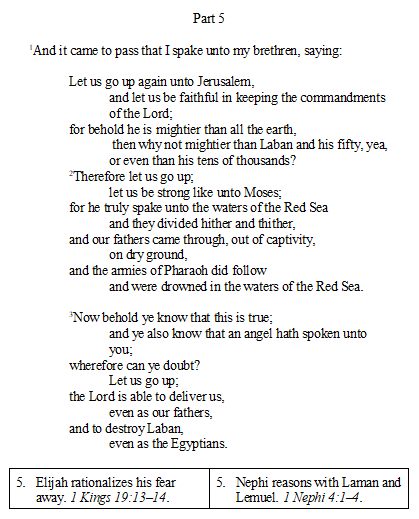

Part 529

What happens in Part 5 is the same thing that happened to Elijah. Elijah reasoned through his fears just like Nephi reasoned through them with his brothers. The logic in Nephi’s argument is easy to see, but one must read between the lines to understand what is happening when reading account about Elijah.30

Nephi’s logical argument is the essence of revelation or the operation of the Spirit according to this story. The revelation is the appeal to the older brothers on account of the Lord’s control of the elements, the need to be strong like Moses, and the fact that an angel had spoken to them. Spoke via a storm—figuratively or literally—just like Elijah.31

The reference to Moses presages the killing of Laban; indeed, Nephi makes the impending death of Laban explicit in Nephi’s retrospective of this interaction with his brothers. He says, “[T]he Lord is able to deliver us . . . and to destroy Laban . . . .” Nephi analogizes to the deliverance of the children of Israel from the pursing Egyptians as they departed Egypt with Moses. In other words, Nephi is saying he went into Jerusalem with the idea of killing Laban in his head, killing him for the deliverance of his family. This would be the same, then, as the Lord destroying the pursing Egyptians.

Laman and Lemuel were certainly not happy with Nephi’s presumptuousness, but they acceded to Nephi’s return for the plates in pursuit of their ulterior motives: they hoped for Nephi’s demise, a good thing for them. It must be remembered that their antipathy was such that they immediately sought Nephi’s death after Lehi died, so they were constrained from killing Nephi while Lehi lived. The sought Nephi’s death for the same reason they hated him on this mission to get the plates: is assumption of leadership.32

Having returned to the walls of the city, Nephi writes the dènoument to this story, Part 6, and Part 6 ALSO parallels Elijah’s experience.

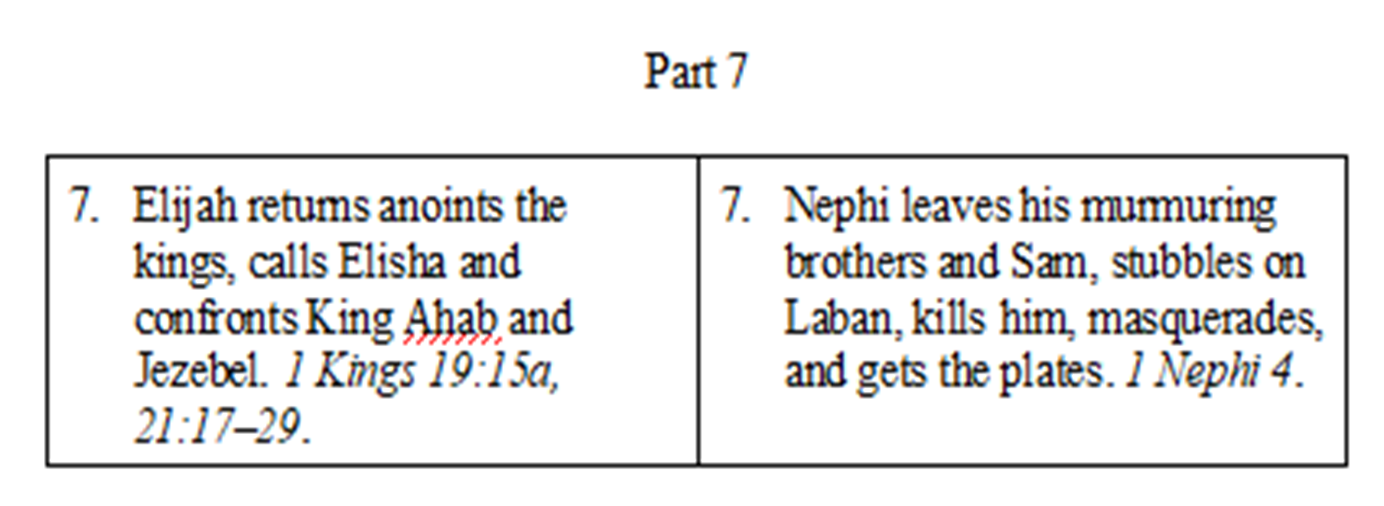

Laman and Lemuel were persuaded enough by Nephi’s reasoning that they returned with him to the wall of the city so Nephi by himself could venture the third attempt to obtain the plates. Nephi, of course, had to figure out what to do because the Spirit would no more tell him what to do than the Spirit will violate anyone’s free agency by giving instructions. Thus, Nephi’s experience, again, parallels Elijah’s, which is found in the seventh parallel.

The seventh parallel with Elijah seems to diverge somewhat at this point. After reasoning through his situation, Elijah knows what he is to do, being told what to do by the Lord, but the metaphysical paradigm of the Hebrews requires this instruction to means that Elijah had figured out what to do. He was to anoint a king for Israel, a king for Judah, and prophet to follow in his stead, the prophet Elisha. Of course, Elijah no more knew the particulars of how and where he was to do what needed to be done than Nephi knew how he was to accomplish his task: get the plates. So Nephi’s return for the plates parallels Elijah’s return to Israel.

Part 7

Elijah’s return to Israel and King Ahab had an affect. Ahab humbled himself, so the Lord did not work His wrath against him, waiting to destroy his son.33Nephi’s story is different, because Nephi kills and masquerades as Laban to obtain the plates.

The actual killing of Laban is an allusion to David taking of the head of Goiliath.34. There can be little doubt it did not really happen; after all, it would have been a bloody mess making Laban’s clothes unwearable. But how he died is not the important part of this. It is Nephi’s reasoning process that is important, because this reasoning, Nephi’s own thoughts, are equated with the the word of the Spirit.35 Nephi’s own thoughts, using the Hebrew metaphysical paradigm, are the Spirit.

Nephi’s rationalization for killing Laban is consistent with his personality type. Nephi was analytical, not emotional, so had no second thoughts about killing Laban. The Church video on this scene is far more dramatic than the event probably was, but I like movies where the bad guy dies, so I really like this dramatization.

This has all of the elements of a good dramatization, including scenes and dialogue not present in the book. The music is good. It builds tension. There is this mystical man’s voice, too, rather than Nephi’s own thoughts. because someone must have concluded that the Spirit, captialized, on this instance must be male.36 Who would not like this video? Not particularly true to the message being conveyed about how the Spirit operates, even misleading in this regard, but it is a guy flick and I like it. Although, I wish the actor playing Nephi played him more like he was.

Like the Hebrew metaphysical paradigm, using the pattern of Elijah’s revelatory experience to underscore Nephi’s own is typical of the Hebrew/Nephite approach to writing. Patterns are repeated in the scriptures as a a comparative figure of speech. Nephi’s still-small-voice experience is like Elijah’s, which adds the numinous aura of Elijah’s experience to Nephi’s. This employment of typology is part of biblical literature.37

The Book of Mormon contains two more allusions to Elijah’s still-small-voice experience. The second allusion involves the missionary efforts of Nephi and Lehi circa 30 bc.38Nephi gave up the judgment seat to preach, so it can be inferred that these were well-educated men. Indeed, both Nephi and his brother were well-instructed by their father Helaman and able to “preach with great power [knowledge] . . . confound[ing] many of [Nephite] dissenters.” Moreover, they spoke to the great “astonishment of the Lamanites, to the convincing of them . . . of the wickedness of the traditions of their fathers.” They were not so well received, however, in the land of Nephi. So they were thrown into jail without food and water because the Lamanites intended to kill them. But things changed when their captors went to get them. There is this fire that does not burn them,39the Lamanites are “struck dumb with amazement,” and there is something like a volcanic eruption with associated earthquakes and darkness from the ash, resulting in “an awful solemn fear.”

The Doctrine and Covenants says the killing of Laban was in accordance with the principle of family protection allowed by the Lord.40 The application of this principle, a three-strikes-you’re-out rule, does not readily appear because Nephi and his brothers were only threatened by Laban two times, not three. The context and what is not said but necessarily implied in the Book of Mormon resolves this dilemma. Laban must have been, by virtue of his office, the one who dealt with traitors; in other words, the direct threat of death that forced Lehi and his family to flee was the threat of Laban, the captain of fifty who was, no doubt, exercising marshal rule and would have killed Lehi and his family for preaching the traitorous notion that the Lord would abandon Jerusalem so that it would fall to Nebuchadrezzar’s attack. Strike one. The encounters of Laman just asking for the plates—strike two—and, then, the brothers took their precious things to Laban to buy the plates, resulting in Laban’s cohort pursing them to kill them. Strike three. These three strikes had to be written into the story to comport with the principles of family protection.

The fact that Laman is characterized as a robber is also important. The robber lived outside the city and the law—an outlaw—and was subject to being killed on sight without the normal protections afforded someone that was living within the law. Laban and the other leaders of the city had, no doubt, already determined that Lehi and his family were traitors who should be killed, but this additional characterization of Laman as a robber highlights the fact that they knew Lehi was now living outside the city and its environs. They were outlaws. As such, there can be no doubt that attempts would be made to hunt them down and kill them, and the appearance of one of these outlaws in the city asking for the plates would have incited Laban to send out a posse. Lehi and his family were in very real danger.

There can be little doubt Laban was a wicked man because of what Ezekiel records about the wickedness of the elders. The night he was killed he had been “out by night” with “the elders of the Jews.”41Ezekiel had a vision on September 17, 592 BC, that included a description of the wickedness of the “seventy men of the ancients of the house of Israel.”42Ezekiel sees the idolatrous practices they performed in the dark.43While it is not clear that these practices were performed in the night as opposed to the darkness of rooms without windows, the wickedness of the elders of the Jews was fundamental to the Lord’s decision to end the probationary period for these people. If, as appears to be the case, Laban was associating with these elders in their wickedness, the decision of the Lord resulting in the termination of his probationary state and his resulting judgment is nothing but an expected result.

Zoram was a slave of probably Canaanite descent because”Zoram is an Aramaic word meaning “a strong, refreshing rain.”44Being a slave he would have been very willing to go into the wilderness with Nephi and his brothers rather than go back to Jerusalem and have to face explaining what happened to Laban, and the promise made to him was that he would be a free man, not a slave.

And I spake unto him, even with an oath, that he need not fear; that he should be a free man like unto us if he would go down in the wilderness with us. 45

How Nephi was able to pass himself off as Laban must understood in the context of relationships between slaves and their masters. It is probable that Zoram, very much the social inferior of Laban, was just not permitted to even look directly at Laban. It was probably death for him to do so. During the 19th century, for example, servants in the homes of aristocracy were not permitted to look at their masters, and slaves in the south were much more restricted in their interaction with their masters.

Notwithstanding the fact that Zoram was able to live as a free man, however, he and his posterity continued to have a separate identity throughout the Book of Mormon history. For example, at the end of the book we read:

And it came to pass in this year [circa aAD 322] there began to be a war between the Nephites, who consisted of the Nephites and the Jacobites and the Josephites and the and the Zoramites; and this war was between the Nephites, and the Lamanites and the Leumuelites and the Ishmaelites. Now the Lamanites and the Lemuelites and the Ishmaelites were called Lamanites, and the two parties were Nephites and Lamanites.46

The return by Nephi and his brothers for the plates of brass is a singular event, something Joseph Smith would probably not have included in the Book of Mormon because the plates reflect the genealogy of Lehi and, later, Ishmael, as being from the house of Joseph. Lehi being descended through Mannasseh47and Ishmael being descended through Ephraim. Joseph Smith would have probably not been a sophisticated enough scholar of the Old Testament to recognize that the division of the Israelite nation into two kingdoms after the death of Solomon resulted in the relocation of the faithful from the northern tribes to Jerusalem. In particular, the tribes of Simeon, Ephraim and Mannasseh migrated to Judah to escape the idolatry introduced into the Northern Kingdom by Jeroboam, an Ephraimite. The great inter-tribal rivalry resulted in Jeroboam, who had been told by the prophet Ahijah that he would be the ruler of ten of the northern tribes, returning to the northern tribes after the death of Solomon where he was elected king as the northern tribes seceded from the south where Rehoboam, Solomon’s son, continued the oppression of the northern kingdoms. The result was the fertile conditions that resulted in the split between the two kingdoms. With the split, though, it became necessary for a new political-religious form of government, a replacement for the state religion that had theretofore governed the house of Jacob. When Jeroboam set up this new, counterfeit religion, a counterfeit that included new places of worship—it may well be that proto-Judaism, likewise, had temples throughout Judah—since Jerusalem and the temple was no longer accessible to them, many of the faithful fled the north, including large numbers of the tribes of Ephraim, Mannasseh and Simeon. The result was that those of the northern tribes that dwelt in the cities of Judah were ruled by Rehoboam. 48 Large numbers of these people had to flee to the south to escape the religious persecution that would have resulted if they had stayed.49

Endnotes

- The Church has posted a video on YouTube dramatizing the events of 1 Nephi 3–ch. 5.

The video is a a dramatization that fails to capture the tenor of the events related by Nephi; indeed and as will be explained, infra, the video is misleading insofar as Nephi’s intended message of to be derived from these events.

- This table is adapted from Noel B. Reynolds, “Nephi’s Outline,” BYU Studies, vol. 20, no. 2 (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 1980).

- Yoram Hazony explains the inseparability of thought from the object or spoken words in the Hebrew paradigm. Yoram Hazony, The Philosophy of Hebrew Scriptures (New York, Cambridge University Press, 2012), at 206–211, 231–232. (Hazony is Provost of the Shalem Center in Jerusalem and a Senior Fellow in the Department of Philosophy Political Theory and Religion.) Hazony addresses the coalescence of thought and object in the Hebrew philosophical construct, which is contrary to the disjunctive treatment in the Greek construct, which infuses Western ideas, of the thought of something being different than the object. In the Hebrew construct just thinking something is the same as hearing it or seeing it. Moreover, truth in the Hebrew way of thinking is the conformity of one’s words with reality over time, the test of truth. Thus, when the scriptures say the Lord or an angel spoke to a person, the speaking is or may be the same as the person thinking what the Lord would say. And, if true, the Lord or angel would, of course, say that. This difference between Oriental thought and Western thought affects how one must read many things in the Book of Mormon, and this recognition allows one to rationalize or understand what would otherwise seem unbelievable.

Compare, for example, the word of the Lord to Lehi in his dream as recorded in chapter one. (The unfortunate chapter division between chapter one and chapter two separates what Lehi understood as a man and what he was told in his nighttime vision, an inapt disjunctive. Lehi, after all, was sentient enough to recognize that his life was in danger because of the things he was teaching the people; indeed, other prophets warning the people of the same things had been executed as traitors. Thus, his dream where the Lord tells him to leave Jerusalem or die is predicated on what Lehi he knew would happen, but it is characterized in Nephi’s record as a vision with the Lord speaking. Of course, there is no difference between the righteous man’s thoughts and the word of the Lord in the Hebrew paradigm, so Nephi’s record is accurate, albeit misleading to the Western mind assumes or sees a disconnect between spiritual and physical. What happens when there are seeming conundrums—how could Laman and Lemuel see/talk-to and angel and not desist the dissent?—are easier to resolve from the perspective of the Hebrew metaphysical paradigm.

- Cp. Lehi’s vision as recorded in chapter one.

- The third attempt begins with 1 Nephi 3:26 and ends with 1 Nephi 4:4. Orson Pratt’s 1879 chapter division is unfortunate, as it splits up the story. The first five chapters today were just one chapter when the Book of Mormon was first published.

- Hapax legomenon means a word or form that appears only once in a book. Still small voice is used only once in the Old Testament and only once in its complete form in 1 Nephi 17 where Nephi chastens Laman and Lemuel for being so spiritually insensitive. This hapax legomenon will be examined in conjunction with the posting or 1 Nephi 16–ch. 18.

- 1 Nephi 3:26–27.

- 1 Nephi 3:27.

- 1 Kings 19:9–15.

- 1 Nephi 3:28.

- Interestingly, those who think Laman and Lemuel beat Sam and Nephi with a stick also think the rod in Lehi’s vision of the tree of life was a bannister, not a rod as pictured in the adjacent artwork by Jerry Thomas.

- Moses’ rod or staff plays a major role in the miracles before pharaoh, Exodus 4–10 and during the Exodus. Exodus 14:16. When there was rebellion in the camp of Israel over the right to the priesthood and who the Lord chose, Moses was required to take a rod for each of the princes of the tribes, place the prince’s name on it, and the rod that blossomed determined who it was the Lord chose to assist Moses. Numbers 17:6–10. There are many other references to rods in the Old Testament, including some that are very familiar but seldom considered in depth, like this hendiadys in Psalms 23: “thy rod and thy staff they comfort me . . . .” Isaiah consistently uses rod in a metonymic way, Isaiah 10:5, 15; 11:1; 14:29; and Jeremiah, also, uses the term metonymically. E.g. Jeremiah 1:11, 10:16, 48:17 and 51:19. Micah, a contemporary of Isaiah, refers to such rod in a couplet at where each couplet says the same thing a different way: the Lord’s voice is equated with hearing the rod: ,

Ezekiel, a contemporary of Lehi, understood the metonymic value of rod, and he employed it consistently and ingeniously. Ezekiel 7:10 refers to the rod that led the Jews: pride and wickedness. Ezekiel 19:11–14 refers to: “the strong rods” of Egypt, “And she [Egypt] had strong rods for the scepters of them that bare rule” during the height of her power, but her rods became broken and withered when foreign powers dominated her, id. a metaphor indicating the loss of Egypt’s hegemony, the rod being degraded “so that she hath no strong rod to be a sceptre to rule.” Id.. Speaking of the gathering in the latter days, Ezekiel notes that the Lord will cause His people to “pass under the rod,” Ezekiel 20:37 meaning they will submit to His kingship and follow His gospel. The rod of leadership is degraded to a stick in Ezekiel 21:8–17; the symbol for kingship or the head of the tribe, a rod or staff of wood upon which the name of the tribe was written, Numbers 17. The word translated as tree in Ezekiel 21:10 is the same Hebrew word translated elsewhere, including chapter thirty-seven, as stick, which is easily cut by a sword. This degradation was the result of the wickedness of the people. The staff or rod or scepter of leadership degenerates even further in Ezekiel’s writings when Ezekiel, no doubt borrowing from the figure used in 2 Kings 18:21 and Isaiah 36:6; refers to pharaoh as a “staff of reed to the house of Israel” that splinters and breaks in the hand when rested upon. Ezekikel 28:6–7.

Ezekiel, a contemporary of Lehi, understood the metonymic value of rod, and he employed it consistently and ingeniously. Ezekiel 7:10 refers to the rod that led the Jews: pride and wickedness. Ezekiel 19:11–14 refers to: “the strong rods” of Egypt, “And she [Egypt] had strong rods for the scepters of them that bare rule” during the height of her power, but her rods became broken and withered when foreign powers dominated her, id. a metaphor indicating the loss of Egypt’s hegemony, the rod being degraded “so that she hath no strong rod to be a sceptre to rule.” Id.. Speaking of the gathering in the latter days, Ezekiel notes that the Lord will cause His people to “pass under the rod,” Ezekiel 20:37 meaning they will submit to His kingship and follow His gospel. The rod of leadership is degraded to a stick in Ezekiel 21:8–17; the symbol for kingship or the head of the tribe, a rod or staff of wood upon which the name of the tribe was written, Numbers 17. The word translated as tree in Ezekiel 21:10 is the same Hebrew word translated elsewhere, including chapter thirty-seven, as stick, which is easily cut by a sword. This degradation was the result of the wickedness of the people. The staff or rod or scepter of leadership degenerates even further in Ezekiel’s writings when Ezekiel, no doubt borrowing from the figure used in 2 Kings 18:21 and Isaiah 36:6; refers to pharaoh as a “staff of reed to the house of Israel” that splinters and breaks in the hand when rested upon. Ezekikel 28:6–7.The New Testament and the Book of Mormon use rod as a metaphorical reference, a metonym for leadership. John the Revelator speaks of the Lord by using the words rod of iron. Revelation 2:27; 12:5; and 19:15.

Simply put, rod is a metonym for leadership or the leader because the rod or staff is such an incident of leadership that it cannot be separated from this office in much the same way a king’s scepter or crown is associated with his regal role.

- 1 Nephi 15:24.

- D&C19:15 (“repent, lest I smite you by the rod of my mouth”).

- This parallel is addressed in more detail in conjunction with Nephi’s revisit of this subject in 1 Nephi 16:6–ch. 18.

- 1 Kings 19:9.

- 1 Kings 19:10–14.

- As discussed below, one can get tangled up with inconsistencies if one assume that the Lord, Himself, actually passed by the mouth of Elijah’s hiding place. The Hebrew metaphysical construct makes one’s own thoughts the word of the Lord if they are consistent with what the Lord would say. Likewise, the voice of an angel is the voice of the Lord. Indeed, the Lord has said that the voice of one of His servants is the same as his own voice.

What I the Lord have spoken, I have spoken, and I excuse not myself; and though the heavens and the earth pass away, my word shall not pass away, but shall all be fulfilled, whether by mine own voice or by the voice of my servants, it is the same.

D&C 1:38 (bolding added); cp. Moroni 10:8.

It is, perhaps, this reality—that what a servant or an angel says is the same as though the Lord has said it—that explains the use of so many indefinite pronouns when it comes to something the Lord has said.

- William Harmon and C. Hugh Holman, A Handbook to Literature, 7th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1996) s.v. dramatic structure.

- 1 Kings 19:12a.

- 1 Nephi 17:45–46.

- “[I]n the orations of the prophets of Israel, wisdom gained from experience, and from reasoning based on experience, at times becomes interchangeable with having heard God’s voice. . . . [T]here seems to be no boundary at all between that knowledge which is native to individuals and that which is granted by God. Yoram Hazony, The Philosophy of Hebrew Scriptures (New York, Cambridge University Press, 2012), at 231–232. Hazony’s discussion of the inseparability of thought from object or spoken words is at 206–211. Hazony is Provost of the Shalem Center in Jerusalem and a Senior Fellow in the Department of Philosophy Political Theory and Religion.

- The literal translation of the Hebrew record of Elijah’s experience and this particular hapax legomenon is discussed in conjunction with 1 Nephi 17:45, the subject of a future blog. Suffice it to say here that the Hebrew translated as still small voice in 1 Kings 19, is translated differently when this Hebrew language is used in the few other places it is used in the Old Testament. These other translations make it clear that still small voice refers to Ezekiel’s thoughts, his reflections.

- D&C 129 says angels are either resurrected beings or the spirits of just men made perfect, those who are not yet resurrected. There were no resurrected beings six hundred years before Christ, the first to be resurrected, so an angel actually appearing would have appeared in glory, because that is the only way the spirit of a just man made perfect can appear. The only angels who visit the earth or those who have or will dwell on the earth, D&C 130:5, and the vision of the Lord is with spiritual mind, not the natural mind. D&C 67:10–13. Indeed, one less than perfect cannot abide the presence of a ministering angel’s glory. Id.

- The rod-beating video can be viewed above.

- Wroth is defined as moved to intense anger: highly incensed. Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged, s.v. wroth, accessed October 24, 2019, http://unabridged.merriam-webster.com. A synonym for wroth is apoplectic.

- 1 Nephi 16:36b–38 17:20a (bolding added).

- D&C 121:26–27b (bolding added).

- 1 Nephi 4:1–4.

- Reading between the lines is the subject of a book by Arthur M. Melzer, Philosophy Between the Lines, The Lost History of Esoteric Writing (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2014). The Bible has different levels of meaning that must be read from different perspectives, and it must be remembered that what was written was in aid of an oral presentation. Emphasis and tone of voice matter. Elijah answers the same questions before, 1 Kings 19:10, and after, 1 Kings 19:13b–14, the manifestations of the Lord powers in the wind, earthquake, and fire. The before answers should be recited with a tone evincing the obvious, matter-of-fact reality Elijah confronted, but the after answers are to be spoken with wry irony. Elijah recognizes the superficiality of his excuses, so he returns to face Ahab and Jezebel.

- The Apostle Paul converted people by his reasoning. “And Paul, as his manner was, went in unto them and three sabbath days reasoned with them out of the scriptures.” Acts 17:2. Accord Acts 18:4, 19; Acts 24:25; cf. Acts 28:(“the Jews departed, and had great reasoning among themselves.”) Samuel reasoned with the people, 1 Samuel 12:8; the Lord asks Isaiah to reason together with him, Isaiah 1:18; the Lord says he will reason with the saints as he did anciently, D&C 45:10, 15; missionaries in the early days of the Church were told to preach by reasoning, D&C 49:4, D&C 66:7, D&C 68:1; the Lord enjoins reasoning so that it leads to understanding, D&C 50:10–12, D&C 61:13; gospel sent forth by reasoning, D&C 133:57.

- 2 Nephi 4:13, 5:1–3.

- 1 Kings 21:25–29.

- 1 Samuel 17. Goliath was a giant, just Laban. Goliath had been stunned by a stone to his head, so he lay on the ground unconscious, which allowed David to cut off his head and take his armor. Decapitation, though, was a particularly ignominious way to die, which both Goliath and Laban deserved.

- It is not clear that the sord sprit should be capitalized in this sentence. The spirit is not modified the expected phrase, of the, if the reference is to, for example, the Holy Ghost.

- As noted in the first blog postings for this blog, there is a substantial scriptural basis for concluding that the Holy Ghost is female and no real scriptural basis for concluding otherwise.

- There are other examples in the scriptures of such patterns. The destruction of the city of Ammonihah told in Alma 8-ch. 16 is consistent with the Mosaic Law calling for the destruction of wicked cities, Deuteronomy 13:12–17. Moreover Alma’s preaching was in three cities: Gideon, Alma 7; Melek, Alma 8; and Ammonihah. A third part of those rejected his words, which is analogous to the third part of the host of heaven who rejected the Father’s plan in the pre-existence. Abraham’s near sacrifice of Isaac, Genesis 22, is a type for the death of the Savior. There is an article in BYU Studies, vol. 32, no. 4 (1992) by Jackson, Bernard S., “The Trials of Jesus and Jeremiah.” The thesis of this article is that the accounts of the Savior’s trial in the Synoptic Gospels uses the trial of Jeremiah as a literary paradigm; hence, the record in the gospels is as literary as it is historical because the trail is presented to conform to a paradigm the readers would expect and knew well.

- Helaman 5.

- This is similar to the experience of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abed-nego, Daniel 3, except this was an natural phenomenon, probably St. Elmo’s fire associated with volcanic activity. See Wikipedia s.v. St. Elmo’s Fire.

- D&C 98:23–32 (“Behold, this is the law I gave unto my servant Nephi . . . .”).

- 1 Nephi 4:22.

- Ezekiel 8.

- Ezekiel 8:12.

- Nibley, Hugh W., Teachings of the Book of Mormon, Semester 1, (Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research & Mormon Studies, 1993) at 161-162.

- 1 Nephi 4:33 (emphasis added).

- Mormon 1:8–9.

- Alma 10:3.

- 1 Kings 12:17.

- 2 Chronicles 11:13–17; 15:9.